Having narrowly avoided setting up a newsletter on Substack (well, a second newsletter) I’m going to use this blog for a similar purpose.

Not least because the other day I read this…

…and I thought, yes, same.

I’ve also been inspired by Paul Watson in a couple of ways. First, by his monthly round-up of interesting reading, much of which really is interesting for once. And, secondly, by his habit of maintaining a proper RSS feed reader, which is how he manages to stay on top of other people’s blogs.

As a result, I’ve fired up Feedly and given it a spring clean.

That is, I’ve deleted all the blogs and websites I followed about a decade ago – because most of them are now either defunct or degraded beyond belief – and added a bunch of new and active blogs.

Many of those I cribbed from Paul’s blogroll but I also had success asking people on BlueSky to let me know about their own blogs, or suggest others they liked.

I’m especially interested in:

- hauntology

- folk horror

- architecture

- cities

- books, films, music

- graphic design

- content design

Do let me know if you have a blog in that territory, or know of a good one by someone else.

In lieu of a newsletter, I’m also nudging people to subscribe to this blog, so they’ll be notified when I update it. So, uh…

A new favourite blog is Stephen Prince’s A Year in the Country which examines various hauntological and folk-horror-related texts in serious detail, drawing unexpected connections between them.

In fact, I’ve been enjoying it so much, I bought the latest print-on-demand anthology of recent writing which I’ve also been reading before bed.

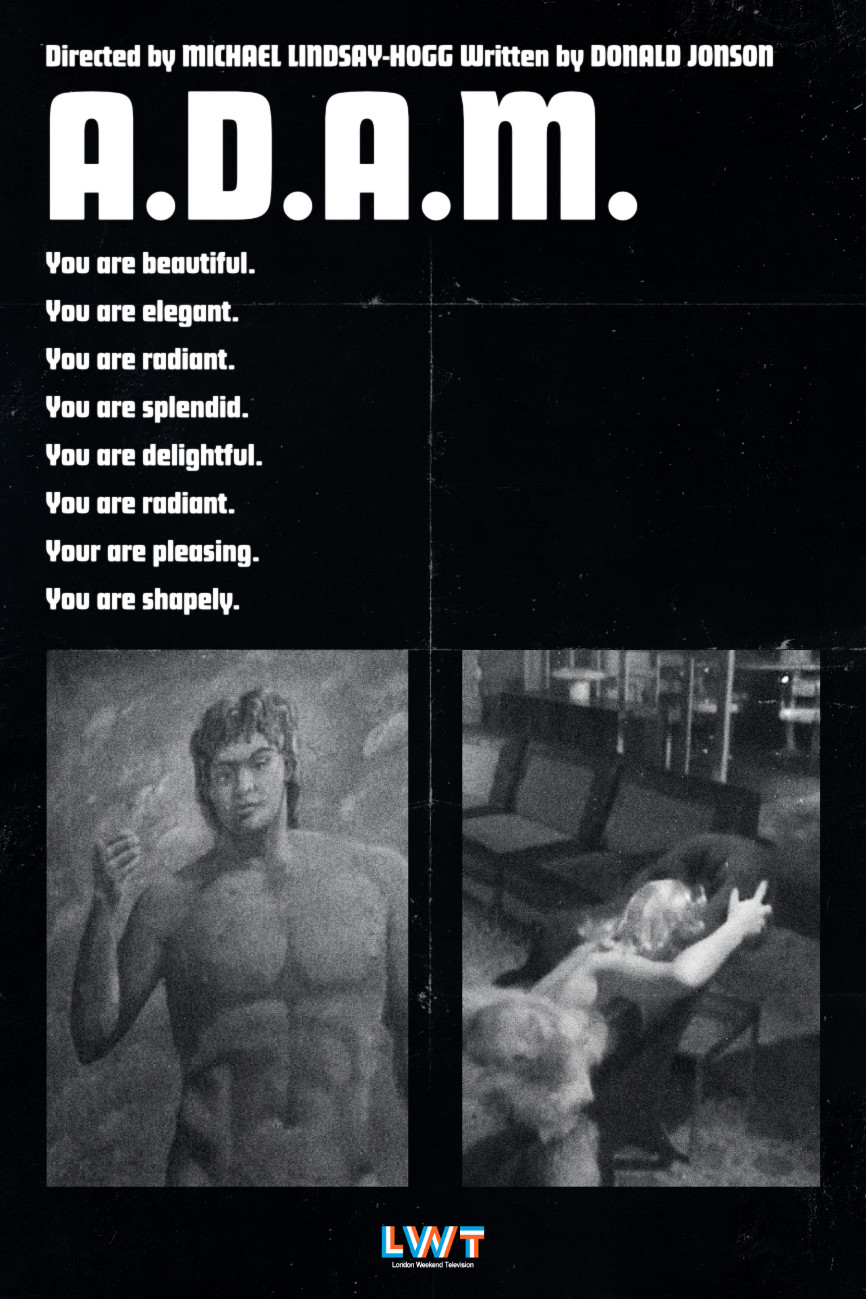

That, in turn, led me to A.D.A.M., a one-off play broadcast on ITV in 1973 as part of its Sunday Night Theatre strand.

It’s about a disabled woman (Georgina Hale) whose scientist husband builds her an electronically controlled house with a voice-activated AI helper. Predictably, perhaps, stuck at home together all day while hubby does Serious Government Work, A.D.A.M. and Jean form an intense and unhealthy relationship.

I found it fascinating and rather enjoyed its paciness, at 53 minutes. Of course it has gained new relevance in the age of Alexa and ChatGPT. In particular, with recent stories of people becoming infatuated with avatars in AI dating apps, there was particular resonance in a scene where Jean writhes naked on a chaise longue while A.D.A.M. robotically recites compliments she’s taught him.

My short review is on Letterboxd, where I try to log every film I watch. Jon Dear, an expert in televised horror, was less impressed than me:

“[In] a TV play that comes in under an hour, a two and half-minute sequence that is essentially two people walking through a doorway comes across as some fairly extreme padding. As this is only the second scene, it doesn’t bode well.”

Oddly, and pleasingly, A.D.A.M. is available for anyone in the UK to watch for free via the excellent BFI Player, so you can make up your own mind at little cost. If nothing else, the opening five minutes are a wonderfully moody piece of grey 1970s British grot.

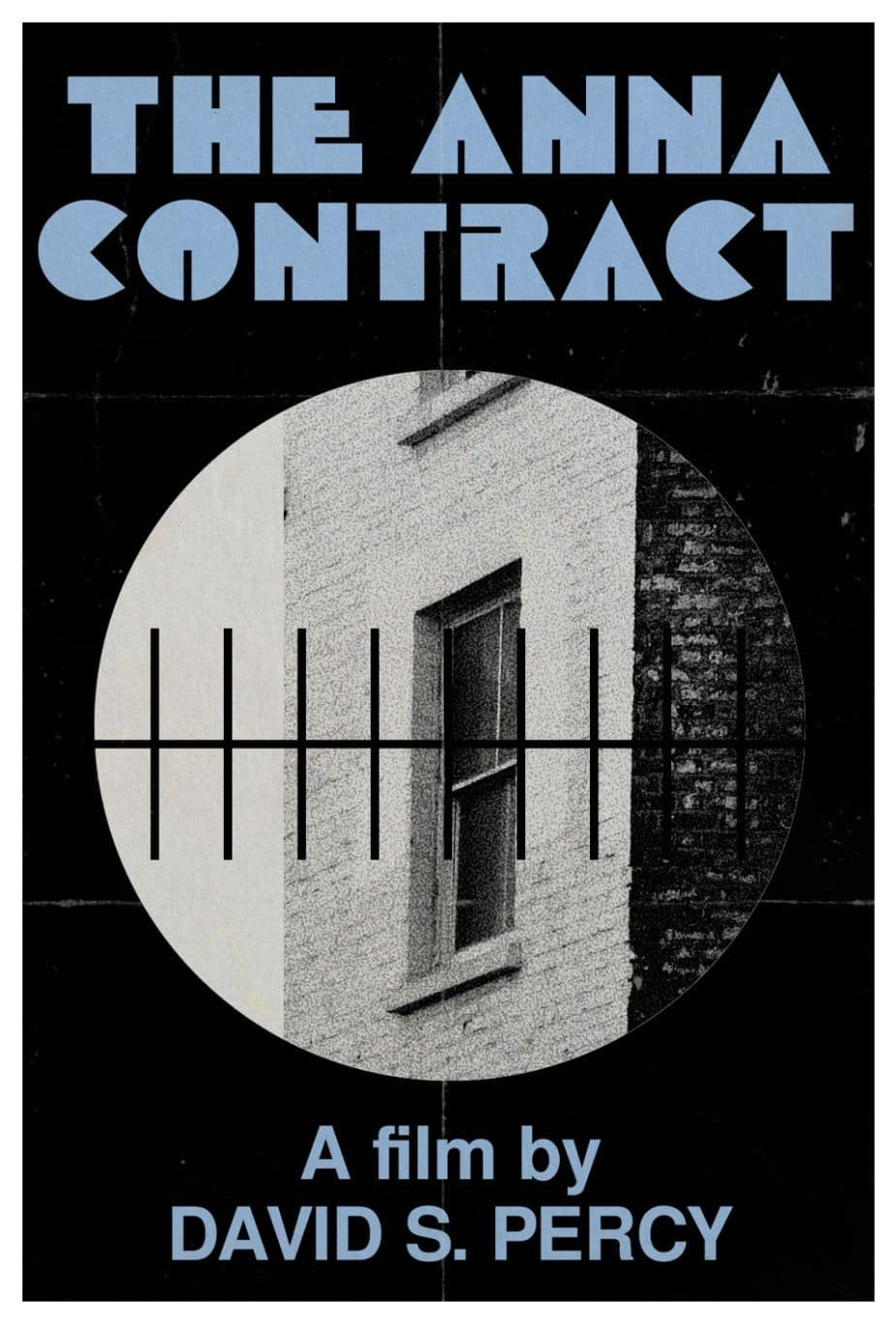

I was also moved to design a new poster for the film, very quickly, because the default one on Letterboxd was so crappy. Fan made posters are discouraged at The Movie Database but I’ve contributed a few where there really wasn’t otherwise a good alternative.

I love it when reading one thing leads me to read another which leads me to watch something else which prompts me to make something – however trivial. That’s what it’s all about.

Integrating music making into my life

I’ve also been trying to work out how to make more music, just for fun, in a way that fits around my day job, my relationships, and my other hobbies.

The latest effort is to actually spend time playing my guitar and learning to play particular songs, in part or in whole.

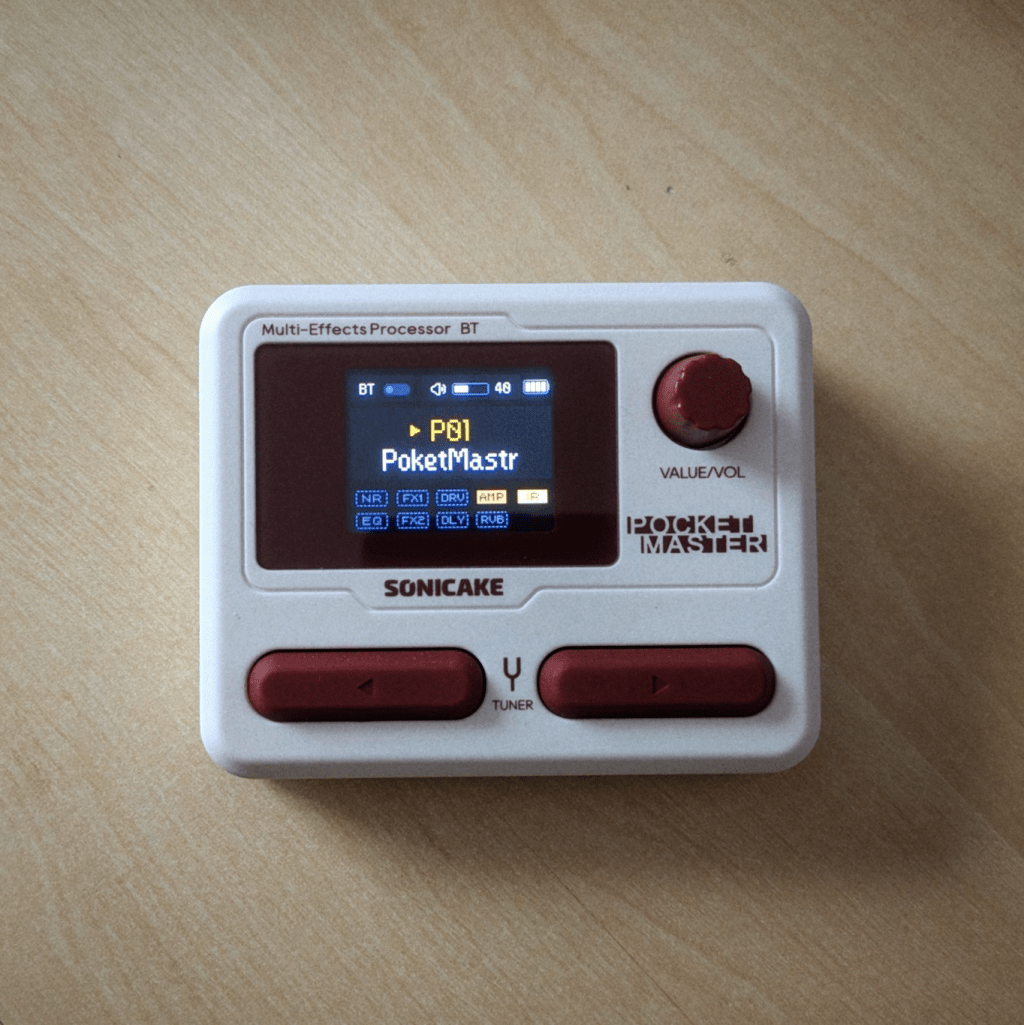

I’m being helped with this by a new gadget, the Sonicake Pocket Master, which cost about £50, has a headphone jack, and among other features can convincingly (to my ears) recreate the sound of playing through various amplifiers.

Last night, I spent about an hour and twenty minutes learning to play ‘September Gurls’ by Big Star for no particular reason other than that for about an hour and twenty minutes I didn’t think about anything but ‘September Gurls’ by Big Star.

It helps, I think, that thanks to the headphones other people can’t hear my playing badly, so I’m able to stick at it until it actually sounds good.

Writing weird stories

I’m continuing to work on my next collection of short stories in the background and seeking input, through blogs, books and films, as set out above, is helping enormously.

I’ve actually got drafts of a full set of stories but I really want to have more than enough so I can (a) pick the very best and (b) try to pull out a theme.

One of my theories for why Municipal Gothic continues to outsell Intervals of Darkness is that the former has a stronger proposition which is further underlined by the brutalist tower block on the cover.

While I’m working on Title TBC please do take a look at those earlier collections and also check out the selection of stories here on the blog.

I’ve also been considering turning those free stories, and some other bits I’ve written for zines, or never published at all, into a sort of bargain B-sides and offcuts compilation.

I always loved those as a teenage music collector because they were both cheaper than ‘proper’ albums and tended to have weirder stuff on them.

What do you reckon?

Lois the Witch

Finally, I’m going to recommend the novella Lois the Witch by Elizabeth Gaskell, from 1859. It’s been rereleased as a cute little minimalist Penguin paperback which I picked up on a whim at Bookhaus in Bristol.

It tells the story of a girl who is sent to New England to live with relatives when her parents die and finds herself at the heart of the Salem witch trials.

In the middle of a heatwave this description of the spookiness of 17th century Salem in winter hit all my buttons:

Sights, inexplicable and mysterious, were dimly seen – Satan, in some shape, seeking whom he might devour. And at the beginning of the long winter season, such whispered tales, such old temptations and hauntings, and devilish terrors, were supposed to be peculiarly rife. Salem was, as it were, snowed up, and left to prey upon itself. The long, dark evenings, the dimly-lighted rooms, the creaking passages, where heterogeneous articles were piled away out of reach of the keen-piercing frost, and where occasionally, in the dead of night, a sound was heard, as of some heavy falling body, when, next morning, everything appeared to be in its right place – so accustomed are we to measure noises by comparison with themselves, and not with the absolute stillness of the night-season – the white mist, coming nearer and nearer to the windows every evening in strange shapes, like phantoms, – all these, and many other circumstances, such as the distant fall of mighty trees in the mysterious forests girdling them round, the faint whoop and cry of some Indian seeking his camp, and unwittingly nearer to the white men’s settlement than either he or they would have liked could they have chosen, the hungry yells of the wild beasts approaching the cattle-pens, – these were the things which made that winter life in Salem, in the memorable time of 1691-2, seem strange, and haunted, and terrific…

Photography

Finally, I’m still taking photos, and currently enjoying trying to imitate Daidō Moriyama. See the main image above for an example.

Moriyama’s style is high contrast black and white, shot from the hip, often askew or otherwise technically ‘bad’, and yet full of vigour and interest.

The murkiness of his photos is half the fun, forcing you to stare a little harder to understand what you’re looking at. Which may well just be a bin bag blowing down an empty street.