When they’ve built flats or superstores on the last of our wastelands, where will stories happen? Where will we go to play dangerous games?

Think of a 1970s British crime drama and you might well picture Jags and Ford Granadas chasing each other round nowhere spaces strewn with rubbish and ruins.

And any number of films stage their denouements on wasteland – because that’s where you end up when you’ve nowhere else to run.

It is a blank space, an urban version of the wild west, where confrontations between goodies and baddies can play out without civilians getting in the way.

It’s perhaps no surprise that the popularity of the word began to soar from the 1920s onward.

Until then, the life of cities took place in their centres – factories, offices, housing, ports and public transport.

But in the 20th century, that began to change.

Wasteland is primarily a product of the decline of industry. In his 1969 book Derelict Britain John Barr explained the extent of the problem of wasteland in post-war Britain:

First of all, industrial wastelands are a visual affront. They offend the eye, they offend what is one of the world’s most civilised landscapes… To tolerate dereliction spattering that landscape, to expect people to live amidst dereliction, is not civilised… Derelict land, and the industrial junk left behind when industry has made its profit and fled, is dangerous to life.

There was also the clearance of ‘slums’ and the movement of the population out to suburbs and new towns.

And, of course, there was World War II. The Blitz created spectacular wastelands in the hearts of cities such as London and Bristol.

T.S. Eliot’s 1922 poem The Waste Land (significant ‘the’, wasteland as two words) addresses the collapse of western civilization brought about by the industrial revolution and the technological age.

For the 1979 album Setting Sons Paul Weller of The Jam wrote a song called ‘Wasteland’ which equates industrial dereliction with childhood freedom. It is only there “amongst the smouldering embers of yesterday” that the song’s working class narrator feels free to express feelings of love.

In the atomic age, wasteland also offered a taste of what might be – a vision of what our homes and streets could become with one well-placed missile.

On film, as well as being logistically convenient for location shooting, wasteland represented similar ideas.

In Seance on a Wet Afternoon (Bryan Forbes, 1964) wasteland is vital to the unhinged kidnap plot enacted by Billy and Myra (Richard Attenborough and Kim Stanley) as a promotional stunt for her work as a psychic.

Among tall grass, rusting Nissen huts and the remains of a half-demolished greyhound racing track, Billy prepares for the kidnap by dying his hair and hiding his motorbike.

Then, when he has the child in his custody, he returns to the same place to dump the stolen car and ditch his disguise.

The wasteland is a place between worlds, and between lives.

By passing through this wild space, he is able to leave civilization behind and transform himself from a timid suburban husband into a criminal capable of anything.

In The Small World of Sammy Lee (Ken Hughes, 1963) Anthony Newley plays a Soho nightclub compere who gets in debt with the wrong people.

His desperate attempts to raise money, against the clock, take him from one part of London to another.

Eventually, though, he runs out of road and winds up on a stretch of Thameside wasteland after dark.

There is nobody there to see or care as he is beaten half to death by his bookie’s enforcer.

In Bronco Bullfrog (Barney Platts-Mills, 1969) a young working class man called Del (Del Walker) tries to find somewhere to be alone with his girlfriend Irene (Anne Gooding).

They are frustrated at every turn, with interfering parents denying them privacy in both modernist flats and Victorian terraced houses.

Though it is far from ideal, like the protagonists of Paul Weller’s song, they resort to an inbetween space: a ruined building on wasteland in Stratford, East London. It is dirty, damp, overgrown and covered with graffiti, and this doesn’t work out either.

The Bashers is a remarkable documentary from 1963. Filmed by the BBC in Bristol it depicts the lives of youths in Barton Hill whose neighbourhood has great stretches of wasteland, awaiting the construction of new blocks of flats.

They don’t have much but they do have this remarkable resource and so entertain themselves by building giant bonfires, and battling gangs from rival neighbourhoods.

The authorities didn’t like this kind of thing, of course, and another place we see wasteland is in one of the most famous public information films. Lonely Water from 1973 shows children playing on the edge of a flooded quarry, among rusting cars and other fly-tipped rubbish.

It’s in the gritty crime film that wasteland really comes into its own. Police corruption scandals and tabloid coverage of the Kray twins triggered a cycle of these in Britain from the late 1960s and through the 1970s.

The final act of Villain (Michael Tuchner, 1971) sees Ronnie Kray-alike Vic Dakin (Richard Burton) on the run in the aftermath of a robbery.

He ends up on a vast area of wasteland at Nine Elms in Battersea, being chased through the ruins of a gas works and a British Rail goods depot.

In Sitting Target (Douglas Hickox, 1972) the final scenes take place in a distinct type of wasteland location: a dusty, cluttered transport depot full of workmen’s sheds, parked buses and freight cars.

Here, Harry Lomart (Oliver Reed) is able to pursue his nemesis, using a red jeep to crash into their car time and again, spinning them around a space that already feels half like a graveyard.

Again, the idea seems to be that this is the end of the line. It’s where you end up when there’s nowhere else to go and where, if you’re lucky, you might just about be able to lose yourself.

This isn’t uniquely British. We see similar settings in American crime films from the same period, and in Italy especially. Italian films about tough cops, known as poliziotteschi, invariably include a car chase or shootout on wasteland on the outskirts of Rome, Milan, Turin, or some other città violenta.

When the villain and the tough cop made it to British TV, the wasteland went with them.

The very first shot of the very first regular episode of The Sweeney, broadcast in January 1975, is of a stretch of cracked concrete, where a van races towards a bright yellow Ford Capri. They’re tooling up for a blag, you see, and where else can you do that except on wasteland?

The same episode concludes with a brutal brawl on what looks like a bombsite. It’s like watching boys play cops and robbers and probably not the first time this particular bit of wasteland was used for that purpose.

In 1980, crime drama The Long Good Friday arguably signalled the end of the wasteland era. Harry Shand (Bob Hoskins) is an East End gangster looking to go straight by getting in early on the London docklands property development boom.

In the decades that followed, London would lose much of its wasteland as Canary Wharf rose from the rubble, and other cities have followed the same pattern.

That barren landscape beyond Tower Bridge would have one last starring role, though, with the remains of Beckton gas works doubling for Vietnam in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket.

Now they’re almost gone, some of us have started to feel nostalgic for those wastelands. They were dangerous, mysterious and wide open.

Those that remain, pending development, are invariably locked down tight, with heavy security and surveillance.

For our own protection, of course, so we don’t end up like the victim of a 1970s public information film, drowned or crushed.

And to make sure squatters can’t get in and make use of these otherwise barren spaces to park vans or caravans.

But where are we supposed to have our showdowns now?

Or hold hands amongst the punctured footballs and rusting bicycles?

“Extract from police report number 727a, strictly confidential, unpublished and unavailable. Subject: Sandy Freemont. The last positive sighting was on her way home from a school orchestra rehearsal. This was on Tuesday May 14th at approximately 6:30 in the evening. At about this time her friend Janey Carr places her positively as entering the footpath through the area known as Cromley Woods, a then popular shortcut for several of the children living in Millard Heights…”

In the suburbs of a middle English town, a schoolgirl walking takes a shortcut through a wood. From the undergrowth, she hears the mischievous laughter of children and her name is called. She pauses and then, in a moment of sudden, startling violence, disappears.

These events, accompanied by amplified natural sounds, an off-kilter music box theme and, finally, shrieking strings after Bernard Herrmann, establish the tone of Lindsey C. Vickers’ 1981 British horror film The Appointment.

The rules do not apply here; anything might happen; brace yourself.

It’s possible you’ve never heard of The Appointment. I hadn’t myself until 2021, via a mention by Elric Kane on the Pure Cinema Podcast.

At that time, the only way to see it was via a VHS rip on YouTube. Once I’d got used to it, the video murk and constant hiss only added to the unsettling quality of the film.

Nor was it inappropriate: this film was only ever released on VHS, in the early days of the home video boom.

It was hard to find much information about Vickers online and, in fact, quite a few writers had assumed he was a woman. So I cobbled together my own potted biography from newspaper archives and scraps.

Vickers was born in 1940, brought up in Norwood Green, Southall, London, and educated at Dormers Wells Secondary School and Southall Technical College.

He left school without qualifications and got a job working as a messenger at London Airport (now Heathrow) before moving into film, starting as a cinema projectionist.

He went on to study film at the University of London and became a film assistant at the BBC where he directed a documentary short called ‘Impressions of Richmond’.

He became assistant director to Denis Mitchell before moving to the Government advertising office, COI, where he made a film a week for global distribution.

He worked as an assistant director on a slew of Hammer and Amicus films throughout the 1960s and 70s, including Taste the Blood of Dracula (Peter Sady, 1970) and The Vampire Lovers (Roy Ward Baker, 1970)

In 1978, he was given the chance to write, direct and edit a short film called The Lake which pre-empts the mood, themes and imagery of The Appointment. It’s beautifully shot and highly effective, despite limited resources, and was made available, fully restored, on the 2020 BFI collection Short Sharp Shocks.

The Appointment was Lindsey Vickers’ first and only full-length feature film as director, which perhaps explains why the astonishing opening doesn’t quite connect with the rest of the film.

My suspicion on first viewing was that the first five minutes were shot separately as a ‘sizzle reel’ to convince investors. I’ve since learned that it was the other way round: the intro was shot later to spice up the completed film.

In 1981, the British film industry was in trouble. According to a contemporary article in the BFI magazine Sight & Sound, only 27 features were produced in the UK that year. The Appointment was one of them.

It cost £650,000 to make and was funded in large part by the National Coal Board Pension Fund – resolutely unglamorous.

It was produced by Vickers’ own company, First Principle Film Productions, with hopes of breaking into the US market.

After that startling pre-credits sequence, the narrator disappears, never to return, and we find ourselves, unexpectedly, in a suburban family drama with engineer Ian (Edward Woodward) obliged to break the news to his daughter Joanne (Samantha Weysom) that he won’t be able to attend her school concert.

The opening sequences are calculatedly bland and the performances almost blank.

Edward Woodward, in V-neck and sensible spectacles, chats to his friend, a mechanic, and to his wife (Jane Merrow) with the same dry tone as Jack Torrance speaks to his new employer at the Overlook Hotel.

Woodward consistently defaults to a half-smile. Even so, just as in The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980), everything feels just a touch off.

In an interview he gave in 2020, Vickers said, ‘I live in the supernatural world up here. The World of the uncanny. The world of ‘How can that be?’ We can see that in The Appointment.

Even before anything truly horrific happens, Joanne’s over-strong reaction to the news that her father is going away – only enhanced by Weysom’s eccentric delivery of the lines – puts us on edge.

Where is he going? To give evidence at the inquest following a fatal mining disaster in which his engineering firm was implicated, apparently no more to him than an inconvenience.

After he snaps at Joanne and sends her to bed he spends an uncomfortably long time staring at the door to her room, thinking about turning the handle. Does he often visit her room at night?

Things really get interesting when Ian tries to get some sleep before his early start the next day.

We’ve all been trained to understand that a prowling camera means we’re seeing through the eyes of someone or something; this someone or something is at Ian’s house, moving through the garden, through the door, along the hallways, in the midnight blue.

Time stops – a recurring theme – as Ian dreams that his wife, in a red dress, turns into his daughter, touching him with more than filial affection.

He is woken by a sudden image of a furious barking of a slavering Rottweiler. When he returns to sleep, he dreams again, this time of his forthcoming journey, and his own death.

The film’s long third act answers questions about that dream: was it a nightmare, or a premonition? From suburb to motorway to service station to remote country roads (filmed in Wales) he is stalked by those black dogs in a way that would amount to a decent gag in a less disturbing film.

There are startling images throughout, with distortions of time and gravity, accompanied by equally disconcerting sound design: wind, unexpected echoes, sudden silences, skittering and skipping.

Much weight is added by Trevor Jones’s romantic, melancholy music, interspersed with electronic droning.

When the end comes, it is shocking and surreal, starting with a biblically tempting apple that seems, somehow, to fall upwards and fly away into space.

In a more mainstream horror film, we’d get a Van Helsing, a priest or a policeman – perhaps that narrator from the opening sequence – to explain what’s going on and to conquer the evil.

Here, there’s no such bow-tying. We’re left bewildered and are expected to put the pieces together ourselves.

Is this a story about a poltergeist summoned by a rage-filled teenage girl? Is it about a demon or the devil? Are we trapped in Ian’s dream?

I have my ideas. You’ll no doubt have yours.

This piece was originally written for the defunct British horror website Horrified. Since its publication in 2021, The Appointment has been released on Blu-ray by the BFI, with The Lake as a bonus feature. It also has a commentary by Lindsey C. Vickers along with other bonus features. To my delight, a quote from my piece featured in a press advert for this new release.

Sleeve notes for a Blu-ray box set that doesn’t exist.

In April 1969 the British film director Bryan Forbes became head of EMI Films in the UK. His statement of intent summed up a particular view of the state of the national film industry at the time:

We have gone too far with pornography and violence… There is simply no reason why filthy violence should be dragged into pictures. You do not have to lower your sights to entertain. We must see to it that entertainment does not become a dirty word.

Meanwhile newspapers were full of talk about “the permissive society”. More specifically, they were asking “Has it gone too far?” Here’s Rosemary Simon in an article in the Illustrated London News:

The saddest aspect of the whole situation is the needless waste. Healthy boys and girls who channel their energies into creating a disturbance instead of concentrating on sport, work, or helping in the community… Attractive girls with their whole future before them who, instead of enjoying their youth and eventually getting married, find themselves pregnant and are faced with the tragic alternative of seeking an abortion of of giving birth an illegitimate baby.

Tabloid newspaper The People reported that its readers had come out 4 to 1 against the permissive society based on the sentiment of correspondence received, like this letter:

A housewife has to try to make a happy home knowing her husband is queueing up to go to work beside a see-through, bra-less, mini-skirted girl… that he chats up a topless barmaid at his pub, while he spends the evening at his club watching strip-tease… If he can afford it, a sexy girl will even cut his hair. Unless he is made of stone he must get involved somewhere… A housewife feels hurt, inadequate, dreary and cannot compete. This is where the children begin to suffer. – Mother of four. Name and address supplied.

That’s terrible, said the public. Appalling. Tell me more. Like, what exactly are they getting up to, these dirty bastards?

In this context British films walked a difficult path. They knew people wanted to see films with sexual content, especially if it was transgressive. But couldn’t be seen to condone it.

So they made films which suggested sexual liberation had gone wrong, that perversion was rife, and that this was a serious Problem of Our Age… while also depicting it more or less frankly, with actors who were more-or-less lovely to look at.

Like American films of the 1930s and 40s who had to make gangsters pay for their crimes to justify the preceding hour of swagger and violence, British ones of the late 1960s had to make sure the swingers suffered for their pleasure.

There are a slew of films from 1968 to 1972 that aren’t formally related but which catch a similar mood and bounce off each other.

They sometimes share cast members, or at least types – ostensibly angelic blonde youths frequently feature, for example, as do sexually confident older women, and kinky establishment men.

Most of them are set in and around London and use the city to highlight the contrast between the old world (decaying, Victorian, Gothic) and the new: motorways, modernist towers, coffee bars, discotheques and pop art pads.

Their soundtracks steal from pop music of the period while always being a little too square, more Alan Hawkshaw than Mick Jagger, straight off the library shelf.

As for the tone, it’s about sickness. Yes, they’ll show you pretty young things with their kit off, to varying degrees, but they’ll also make you feel slightly queasy.

Brothers and sisters put hands and lips where they shouldn’t. People sweat and fret, suffering from physical and/or mental wounds. They mix sex and death at every opportunity. And adults frequently behave and even dress like children – which says what about their lovers?

Is it ever sexy? Fleetingly, sometimes, but more often it feels like the aversion therapy Alex undergoes in A Clockwork Orange.

The film that feels to me like the start of this run is Twisted Nerve (dir. Roy Boulting, 1968) starring Hywell Bennett as a baby-faced blonde psychopath called Martin.

Barry Foster plays a lecherous lodger employed in the film industry, who says at one point: “If you want me to sell your crummy films, I say you’ve gotta give it a good dose of S&V. That’s what the public wants. Sex and violence.”

What a disgusting attitude, we are invited to think, before gorging on our own helping of S&V.

At the time, the controversy around Twisted Nerve centred on its treatment of the subject of Down’s Syndrome and its tangling of chromosomal conditions with mental illness. That’s even less comfortable for viewers today.

But it exactly demonstrates the tendency of these films to balance turn-ons with turn-offs. Twisted Nerve starts with Martin engaged in an extended discussion with a doctor about his brother’s incontinence, likely early death and parental abandonment. It’s pointedly bleak.

Martin then adopts, or rather inhabits, an alternate personality – Georgie, a childlike character presumably based on Martin’s observations of his own brother. As Georgie, he stalks Hayley Mills and inveigles his way into her home. He then seduces her mother (Billie Whitelaw) who, remember, is up for it, despite believing that he has the mental capacity of an eight-year-old.

Martin is sick but so is almost everyone else, including his own respectable but uncaring parents.

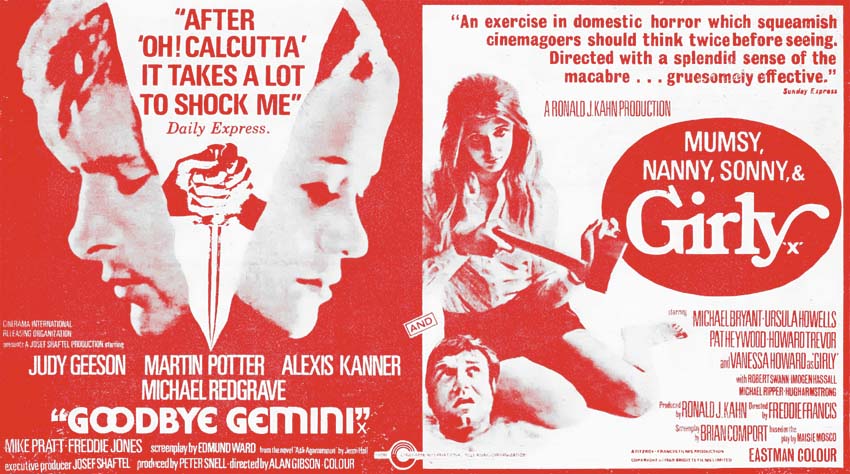

It’s astonishing that two of the key films in this cycle were released simultaneously and often shown together as a double bill. That is Goodbye Gemini (dir. Alan Gibson) and Mumsy, Nanny, Sonny & Girly (dir. Freddie Francis) both released in 1970.

Of the two, Mumsy, Nanny, Sonny & Girly is the better and more interesting film. It tells the story of a strange family – or is it a cult? – living together in a large country house.

The matriarch (Ursula Howells) and her servant (Pat Heywood) run the house while Girly (Vanessa Howard) and Sonny (Howard Trevor) run around in school uniform playing The Game.

To play The Game, you need playmates, so they occasionally go out into the world to seduce or bamboozle vulnerable men into joining them at the house. Those men are imprisoned and played with until they break the (impenetrable, unwritten) rules, at which point they are murdered.

When this film was released in the US it had a new title – Girly – and Vanessa Howard was the focus of the marketing. Dressed as a schoolgirl, the then 22-year-old actress sometimes plays the character as a seductress, and at other times as genuinely childlike. The audience is invited to fancy her, then to feel unclean for having done so.

It’s a grubby, disturbing, slimy film that makes my skin creep in the same way as Death Line, only without the gore. The other comparison might be The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, which also finds horror in twisting the traditional family structure.

Goodbye Gemini is more generic. It opens with rapidly cut shots of a coach arriving in London along the motorway, soundtracked by thumping Hammond-driven rock music. It’s meant to tell us we’re arriving in the big city, in the modern world, but of course it all looks a bit damp and tatty.

Judy Geeson and Martin Potter play cute blonde twins Jacki and Julian. They’re in their late teens or twenties but act younger, often deferring decisions to their teddy bear, Agamemnon. Decisions such as whether to throw the housekeeper who’s supposed to be looking after them down the stairs, for example, so they can enjoy London without restraint.

Julian loves Jacki a bit too much, in a way that’s not healthy. For a while, they share a boyfriend, hippy hipster Clive, who also wants to be Julian’s pimp. To seal that deal, he arranges for him to be raped by two men. So Julian and Jacki arrange for Clive to die. And so on into ever-descending spirals of blood and hysteria.

It’s a sweaty, feverish, unsettling film that tells us sex is a nightmare, love is a sickness, and that only death can set us free. It was also released under the name Twinsanity which is less tasteful but gives a clearer idea of its tone.

There are plenty of other films that fit alongside those mentioned above, many of them included in the excellent book Offbeat edited by Julian Upton, which presents an alternative canon of British film.

I’ve already mentioned Dracula AD 1972 which brings Dracula to modern-day swinging London. Here, the obligatory handsome blonde boy with a black heart is Johnny Alucard (Christopher Neame). His sickness takes the form of a master-slave relationship with Dracula himself. You could take Dracula out of the equation and retool this as a story about a delusional psychopath loose among the hipsters of Chelsea with relative ease. Like Goodbye Gemini it opens with shots of London – jet planes, flyovers, tower blocks – accompanied by pounding rock-funk. The following year’s The Satanic Rites of Dracula, also directed by Gibson, provided more of the same, with the addition of a satanic sex-power cult.

What Became of Jack and Jill (dir. Bill Bain, 1972) has Vanessa Howard, AKA Girly, as one half of a murderous young couple opposite Paul Nicholas. They shag on his granddad’s grave as they plot the murder of his grandmother. Their plan is to scare her to death by convincing her that the young are rioting in the streets and rounding up the elderly.

Unman, Wittering & Zigo (dir. John Mackenzie, 1971) isn’t set in London but transplants swinging London icon David Hemmings to a public school in the country. His pupils, arrogant little bastards, tell him they killed his predecessor and will kill him if he doesn’t submit to their will. As they engage in a battle of wills, the boys stalk and eventually attempt to rape his wife. Sonny from Mumsy, Nanny, Sonny & Girly would fit right in. He might even make a good pal for the unfortunately marginalised Wittering.

Jerzy Skolimowski’s Deep End from 1970 is beautifully made – definitely more art than exploitation. But it still gives us the beautiful blonde boy with a kink in his brain (John Moulder Brown), sexual relationships that cut uncomfortably across age barriers, and sex scenes that are more disturbing than arousing. He plays Mike, a 15-year-old boy who gets a job at a swimming pool in East London. On day one his colleague Susan (Jane Asher) initiates him into a job on the side pleasuring older women in the sauna rooms. He is driven mad by his infatuation with Susan and their complex relationship (she rejects him, then brings him close) leads to the inevitable mingling of sex and death.

The Ballad of Tam Lin (dir. Roddy McDowall, 1970) cuts across sub-genres. The first act takes place in that familiar, slightly square version of swinging London with beautiful young things in mod clothes speeding around in sports cars. The sequence in which they race out of town, past the modern office blocks of London Wall and up the M1, recalls the opening scenes of both Goodbye Gemini and Dracula AD 1972. They are the acolytes of a beautiful older woman (Ava Gardner) who seems to draw strength from their youth. There’s no room for dead weight in her commune-cult, though, and we see that she uses people up and discards them. The second half of the film fits more comfortably into the folk horror bracket, however.

These films are all quite different, I realise, in both intent and quality, but you could pick any two and run them together as an effective double bill.

When I asked people on Twitter about this they suggested a whole slew of other candidates. I’ve compiled those, along with the films listed above, into a watchlist on Letterboxd. Let me know what’s missing.

On film, the post-war British new town is an uncanny space – heaven, hell, or somewhere between, but certainly not quite real.

The idea of the new town was born out of hope and optimism. With population growth, cities half-demolished by the Blitz, and increasingly demanding expectations around quality of life, ordinary working people in Britain needed new and better homes.

The British government set about identifying sites across the UK where large residential towns could be built from scratch, or by drastically expanding existing smaller settlements.

This was revolutionary, contrary to the usual British wait-and-see gradualism, and not everybody was convinced by the idea. It’s certainly difficult to find wholly positive depictions of the new towns project on film outside government propaganda.

Right at the beginning, when the new towns only existed in plans and papers, Basil Dearden directed a film based on J.B. Priestley’s 1943 play They Came to a City. Released in 1944, it’s not explicitly about new towns but rather about the need to reorder British society along fairer lines after the war.

It just so happens, however, that Priestley’s metaphor for this new society is a city. A new one.

Priestley’s script acknowledges that not everyone wants to come on this journey – and those who choose to stay behind have their reasons. Nonetheless, the argument is clear: things need to change and someone needs to have the guts to explore the frontier.

Almost as if they couldn’t help themselves, however, Dearden and Priestley make the new town not only ambiguous but also unsettling, alien and even a little threatening. A supernatural, spiritual force rather than the product of pure bureaucracy.

Dearden’s previous film, Halfway House, had a similar structure – strangers gather to solve an existential mystery – only in that case, the twist is that they have all gone back in time to fix their mistakes. Here, they’ve gone forward, and are being given a chance to prepare for Things to Come.

We never get to see the town, only the giant portal and staircase that lead to it, and the alternately appalled or euphoric faces of the visitors as they return. That makes it all the more unnerving. What on earth can be at the end of that staircase? Surely something more exciting than, say, Harlow.

After the war, the New Towns Act of 1946 triggered the building process. Development of the first wave was focused on London and the South East.

From then on, the idea of the new town as a point of tension – new versus old, planned versus organic, urban versus rural – would be played out on film, consciously or otherwise, time and again.

Some filmmakers were drawn to new towns because, half-built in the 1950s, they offered plenty of unsettling atmosphere off the peg. They were strange spaces. Silent. Disconnected from the world. Alienating.

Literally so in the case of Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass II.

The original 1955 BBC television series features scenes set in a ‘prefab town’ built for workers at the sinister secret facility around which the plot revolves. By the time Hammer adapted it for film in 1957 (dir. Val Guest) the setting was very clearly a more permanent new town, filmed on location at Hemel Hempstead.

It is presented as bleak and windswept, like a colony on Mars. The houses, in rippling rows, are surrounded by moorland. From one angle, it is urban. From another, rural. Both, and neither.

This plays on a feeling that new towns simply should not be. Towns should grow over the course of decades, over centuries – not overnight.

In his 2016 book The Weird and the Eerie Mark Fisher wrote about a container port in Suffolk as “a weird phenomenon, an alien and incommensurable eruption in the ‘natural’ scene”. Its silence, when viewed from a distance, contributes to this sensation. New towns can have a similar effect.

There’s also cold war paranoia in Quatermass II, and a suspicion of anything resembling socialism. The people of the town are unwitting worker drones for alien invaders, their servitude bought with these bland, identical homes, and the promise of food on the table in return for no questions asked.

A later television production, Danger Man, took a more head-on approach to the same idea. In the 1964 episode ‘Colony Three’ John Drake (Patrick McGoohan) is kidnapped and taken to Hamden New Town. (Played by Hatfield.) It’s perfectly clean, perfectly civilised, but of course it’s not an English town at all – it’s an unnamed Eastern bloc country and is a training ground for spies.

This sense of the uncanny, of the new town as an unnatural invader, is even present in ostensibly comic films.

In The Big Job, a not-quite-Carry-On from 1965 directed by Gerald Thomas, Sid James (also in Quatermass 2) plays a gangster who buries the spoils of a robbery in a country field. Fifteen years later, when he is released from prison, he returns to find that a new town (Bracknell) has been built on those very fields – and a police station right on top of his treasure.

It’s a funny setup but it also underlines the pace of change in post-war Britain. Who would expect deep English countryside to become a settled English townscape in such a short span of time? Turn your back and the very fabric of the country will shift.

This leads us to another question: what does the new town bury or replace?

In the American film Poltergeist (dir. Tobe Hooper, 1982) a Spielburbian planned community (housing estate) is built on the site of an old burial ground that was never cleared, which is the source of its haunting.

But almost every inch of Britain is a burial ground or battlefield.

Requiem for a Village (dir. David Gladwell, 1975) is almost a ghost story, or perhaps an example of folk horror, built around the growth of a new town around a country village.

In the opening scenes we see an old man set off from a modern housing estate on the edge of the town, wobbling along on his bike. He negotiates roundabouts and a dual carriageway, eventually finding his way to a secluded village church. While tending the grounds, he has a vision of bodies rising from the graves, returning to the pews in the church. He follows them and so begins a trip through his own memory, and a collective memory of a lost rural life.

The new town here isn’t bad – the houses are large, clean and comfortable. And the past is murky, too, blighted by war, poverty and rape.

But, still, there’s a suggestion that the modern world has rolled concrete, closes and crescents over something richer and more complex. The bulldozer is an existential threat.

A less arty but perhaps no less heartfelt take on some of the same ideas can be found in, of all places, the second film based on the TV sitcom Till Death Us Do Part.

Released in 1972, The Alf Garnett Saga (dir. Bob Kellett) relocates Garnett from the East End of London to a tower block in a new town – Hemel Hempstead, once again. He not only dislikes it but cannot cope with it. It has the trappings of a community, such as a pub, but is configured in a way that leaves him bewildered, imprisoned and humiliated.

At one point, he takes LSD, imagines himself to be a chicken and nearly falls from the balcony: “Out the window, fly away… Open the window, open the cage…”

In an essay translated into English as ‘The Uncanny’ Sigmund Freud actually uses the German word unheimlich – ‘unhomely’. Are new towns homely?

A common criticism of new towns and overspill estates is that they lack soul or character. “Rows of houses that are all the same” are contrasted with the individuality of the buildings found in towns which developed organically over centuries. And because these houses are built in clean, straight-line modernist style, they seem to lack individual texture.

There’s another kind of place they call to mind, especially when seen in their pristine state in films from the 1960s and 70s: the ‘tin towns’ in which the British Army trains for urban warfare. Or, of course, standing sets on studio backlots, whose houses are usually hollow shells.

In both I Start Counting (dir. David Greene, 1969) and The Offence (dir. Sidney Lumet, 1973) the new town is dangerous in another way: as the hunting ground for a serial killer.

I Start Counting makes explicit an alienating quality in new town life. “The rain don’t even fall on us here,” says Granddad, looking forlornly from the window of the family’s tower block flat. The flat is actually a studio set and, painted beige and white throughout, evokes the alien simulation of a bland hotel room where Dave Bowman ends up at the end of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

If the new town feels unreal, like a simulation, then what might that do to the mind of a psychopath already struggling to ascribe real feelings to, or empathise with, his victims? They’re just non-player characters in an open world game.

Then there’s the would-be utopian landscape of pedestrian underpasses, footbridges and green space. A dream in the promotional films made by new town corporations to market themselves to the young city dwellers they hoped to lure. But also appealing to parasites looking for opportunities to kidnap, maim or kill.

In I Start Counting it’s parkland at the end of the bus route – the new town’s weirdly hard edge – where young women are most vulnerable. In The Offence, it’s tunnels running beneath brand new roads where a child-killer strikes.

Built-up but sparse, populated but somehow empty, this new town (Bracknell, again) feels especially psychically dangerous. Look what it does to Detective Sergeant Johnson (Sean Connery): he loses his grip on reality and morality, brooding in his tower block flat and the new-build brutalist police station like a man in purgatory.

New towns are appealing to criminals of other varieties, too. As a composite of both Kray twins in Villain (dir. Michael Tuchner, 1971) Richard Burton plans the perfect payroll robbery to take place on the beautifully empty roads of (yet again) Bracknell.

For the East End villain, this is ideal: do your business out of town, on the wild, distant frontier, with only provincial policemen in your way.

And then, of course, there’s Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971), which used Thamesmead, marketed as “London’s new town!”, to represent a dystopian future.

More than any other film, this cut through the PR and foresaw problems to come. When footbridges and underpasses cease to be cared for, when the gardens become overgrown, and the concrete sickens, the shine can go off a new town pretty fast.

Despite the recurring portrayal of the new town as uncanny, unsettling and alienating, it’s not all bad news. In two notable sex comedies, it’s not a training ground for aliens, spies or criminals but for randy teenagers. It’s a playground. A safe space to practice being an adult.

In fact, rewind: there’s even some of this in I Start Counting. It offers glimpses of a town centre where young people are given places of their own – record shops, cafes, nightclubs – and where there are plenty of precincts and arcades, squares and parks. They’re new and shiny, too, not yet haunted by Alex and his droogs.

In Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush (dir. Clive Donner, 1968) and Gregory’s Girl (dir. Bill Forsyth, 1980) the focus is entirely on the struggles of young men to understand young women.

The bland, clean safeness of their new town backdrops (Stevenage and Cumbernauld respectively) saves us from the heavy ‘issues’ that so often bog down British youth films. We don’t need to think about urban decay when there’s love in the air. In Forsyth’s film, Cumbernauld looks positively Californian, its concrete bathed in golden hour light. Shangri-La.

Christopher Ian Smith’s 2017 documentary New Town Utopia, about Basildon in Essex, gets the balance right. With time, it argues, memories have accrued and traditions have developed. If they aren’t paradise, these Pinocchio towns, have at least achieved their dream of becoming real places.

In 2021, I taught myself to sit down and watch films like I used to as a kid.

Not just easy films, or comfortingly familiar ones, either – films I’d never heard of; often old, sometimes slow, frequently strange.

Through work weariness and pandemic funk I’d drifted into some bad habits: evenings spent watching two or three episodes of some American police procedural or other that I didn’t even like or enjoy. Mentally chewing gum as I waited for bedtime.

Then I moved house and, for the first time in years, my collection of DVDs was where I could get to it. I found discs I’d forgotten I had and which I’d never got around to watching, or not seen in 20 years.

And, as it happened, the winter-spring lockdown was the perfect time to explore.

It wasn’t a resolution, as such. I’m not good with resolutions. But I did find myself thinking, come on, now, Ray – if you’ve got time to watch sodding Bones, which is terrible, you’ve got time to watch The Fifth Cord. How bad can it be? (It was great.)

I also got better at resisting the urge to dither: just pick a film; it doesn’t matter all that much.

Before long, watching films had become a new habit. Or, at least, a revived one, because I used to do this when I was a teenager, too.

Back then, I’d tape films from the TV with the VHS recorder I inherited from my grandmother when she upgraded. I had stacks of tapes, each with two or three films on, carefully labelled.

I’d stay up past midnight watching oddities on BBC2 or Channel 4, and spend Saturday and Sunday afternoons with canonical classics such as Casablanca or The Third Man.

At sixth-form college, I ran the film society, choosing films and writing programme notes for the other five or six attendees to snigger at. (I was a pretentious little berk.)

This year was about scrambling to catch up on a lost decade or two.

To some degree, I’ve trusted the curatorial instinct of labels such as Arrow Films, Indicator, Masters of Cinema and the Criterion Collection. If they’ve bothered to release a film on a pristine Blu-ray disc, you can be sure it will be worth a couple of hours of your time, in one way or another.

Podcasts like The Evolution of Horror, Second Features and Pure Cinema are a great help, too, suggesting films I’d never think of watching if it wasn’t for the enthusiasm of their hosts.

They also led me to books such as Danny Peary’s Guide For the Film Fanatic from 1986, which provided yet more items for my watchlist.

The watchlist isn’t just a scrap of paper, either: it’s on Letterboxd. Using that platform properly for the first time has really worked for me. Making myself log, rate and review each film I watch has kept me focused on my target of watching 150 films this year.

Not every film I’ve seen this year has been a joy – others may love Alice, Sweet Alice but I did not. But learning to sit through the duds, and think about them in context, is all part of the fun.

There’s a long list of films I’ve enjoyed and would recommend on Letterboxd but here’s my top five:

If you only get time to watch one, I’d say I Start Counting was the standout – an unsettling coming of age drama with a serial killer on the side, all set in a post-war English new town.

And if you’ve got recommendations for 2022, I’d be delighted to hear them.

The neighbourhood. Quiet, curving streets where children play in the road, making way now and then for a wood-panelled station wagon or Chevy pick-up. The houses are probably painted white, with white wooden fences, and perfectly green lawns. There might be a paperboy slinging rolled copies of the local daily. TVs are always on and always showing black-and-white movies or Looney Tunes cartoons. Kids have Star Wars posters on their bedroom walls and play games on Atari consoles. Teenagers listen to pop music on chunky Sony Walkmans. There will certainly be tall, tanned dads watering lawns and washing cars and faintly glamorous moms cradling brown bags overflowing with shopping. For dinner, it’s Wendy’s or McDonald’s, accompanied by cans of Coke or Tab for the kids and Budweiser for Dad. And it is always Independence Day, or Halloween, or Christmas – golden hour glow, warm autumn leaves, perfect snow. America is on top, life is good, adventure is just round the corner.

I spent my early years on a concrete council estate in a small town in Somerset but, like Rick Deckard in Blade Runner finding succour in his implanted memories, the images that spring to mind when I think of childhood are often American in flavour. That’s because, like many people my age, I grew up largely in front of a rented Rumbelow’s TV, absorbing the sunny glow of Spielburbia.

Spielburbia is a name for the American suburb as envisioned by Steven Spielberg. It manifests in films he directed such as E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), those he produced such as Back to the Future (dir. Robert Zemeckis, 1985) and others which simply imitated his style in pursuit of a share of his incredible commercial success. As far as I can tell, the term Spielburbia was first used by Tony Williams, disparagingly, in his 1996 book Hearths of Darkness, with reference to Poltergeist, a pop horror film that Spielberg produced and was long thought to have shadow-directed over Tobe Hooper’s shoulder. Williams sees Spielburbia as a reflection of an ‘infantile mindset’. To those living through less than perfect childhoods and, worse, the crushing weight of adventureless adulthood, that is precisely its appeal.

My gateway to Spielburbia was a branch of Ritz Video on the Sydenham Estate shopping arcade in Bridgwater. That’s where my parents rented, in big yellow boxes, also-ran kids adventure films like D.A.R.Y.L., The Boy Who Could Fly, The Explorers and Flight of the Navigator, all of which I saw long before E.T. or Close Encounters. When I talked about this with my brother, he recalled the colour-coding system that dictated the rental price: E.T. was expensive, D.A.R.Y.L. was cheap. So we watched D.A.R.Y.L. and loved it. Television was also important, five- or six-year-old big-budget American movies being the key events in what continuity announcers called ‘a very special Christmas here on BBC1’, or bank holiday matinees.

To a child in Britain in the 1980s, Spielburbia was both familiar and alien. We had kids on bikes. We had fences. We had plastic action figures and even American footballs, for which there was a brief craze in the UK at the tail-end of the decade. But it lacked the scale or glamour. The bikes were rusty non-brands from Halfords. The fences were steel mesh, also rusting. There was no mountain behind our estate – no pine forest or field of corn.

The cinematic Spielburbia came into being, I think, with Spielberg’s first big hit, Jaws, released in 1975. Though set on a tourist island, not in the suburbs, the feel is there in the scenes of Chief Brody’s domestic life and the arrival of tourists on Fourth of July weekend. Spielberg has a delicate touch when it comes to portraying the barely-blessed lives of ordinary Americans – adults and children bickering and laughing together over unmade beds, coffee machines and bowls of sugary cereal. In Jaws, Martin Brody awakes reluctantly and stumbles stiff-legged across the bedroom to check on the kids in the yard. “In Amity, you say yaaahd,” says Ellen Brodie, teasing. “They’re in the yaaahd, not too faaaah from the caaaah. How’s that?” replies Martin. “Like you’re from New York,” says Ellen. While Brodie fields a garbled call about a missing swimmer, his son Michael swaggers into the kitchen and proudly shows off a wound – the result of playing on poorly-maintained back-garden swings against his father’s instructions.

Swings! A minor detail but, oddly, a recurring one in the run of Spielberg’s movies from Jaws to Poltergeist. I’d bet any money his own childhood home had a set. And that mention of New York is important too: this is not New York City, or Los Angeles or Chicago – the default urban settings that define many cult films of the 1970s. The appeal of Spielburbia is that, at least until killer sharks, aliens or sinister government agents arrive on the scene, it is not ‘gritty’ or dangerous. It is – I can’t avoid the word any longer – ‘sleepy’.

Spielberg’s next film, Close Encounters from 1977, develops the idea. Centreing on a family man, Roy Neary, played by Richard Dreyfuss, it grounds the fantastical alien visitation plot with a portrait of a down-to-earth lower-middle-class suburb in Muncie, Indiana. Muncie – the very word sounds like an adjective, something from The Meaning of Liff, perhaps meaning dull or bland. The neighbourhood provides a pointedly sane backdrop against which Neary’s UFO-induced madness plays out. Spielberg delights in the background details: backyard swings, again; dads in shorts washing cars and boats on sloping driveways; children practicing their baseball swings, or riding bikes.

Though set in Indiana, in the American Midwest, it was actually filmed in Mobile, Alabama, in the southeastern US. That Spielberg could make this substitution tells us something: American suburbs are American suburbs, utterly interchangeable. Or, if you prefer, universal. The house that played the part of the Neary home is in a post-World-War-II housing development called Colonial Heights – an arrangement of near-identical single-storey houses along meandering streets designed to go nowhere in particular. It is a classic example of ‘tract housing’.

Tract housing, sometimes known as ‘cookie-cutter housing’, was primarily a post-World-War-II phenomenon. As the US population grew, increasing by 50 per cent between 1940 and 1970, millions of Americans moved from rural settlements into urban and suburban settings. By 1970, there were around 75 million Americans living in the suburbs – more than the entire population of the UK.

This suburbanisation was brought about by the advent of techniques for mass-producing appealing homes, and of heavy-duty construction vehicles which made it possible to clear great areas of agricultural land, wilderness or even desert plains. Hills could be flattened, terracing imposed, and landscapes composed – new spaces into which thousands of individual homes could be dropped with maximum efficiency.

The most famous examples might be the Levittowns built by Abraham Levitt & Sons in New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Puerto Rico and Maryland between 1947 and 1970. The houses were built on production lines and could be erected in a single day.

While many applauded the democratisation of home-ownership this brought, the uniformity of this new suburban architecture – it’s sheer bloody munciness – unnerved some. What had happened to American individualism? A 1950 catalogue for the tellingly named Standard Homes Company entitled Homes for Your Street or Mine boasts that the designs within were ‘standardized to avoid waste… America’s best planned small homes’. The utopian illustrations depicting ‘The Lorain’, ‘The Lexington’, ‘The Wayne’ immediately bring to mind Spielburbia.

These suburbs also came in for criticism from those who saw in them the potential for ever-greater alienation and detachment from society – where were the neighbourhood bars or diners? Where were people supposed to congregate when not at work? Ray Oldenburg, author of The Great Good Place, published in 1989, saw the loss of this vital ‘third place’ from American culture after World War II as the root of many societal ills:

What opportunity is there for two men who both enjoy shooting, fishing or flying to get together and gab if their families are not compatible? Where do people entertain and enjoy one another if, for whatever reason, they are not comfortable in one another’s homes? Where do people have a chance to get to know one another casually and without commitment before deciding whether to involve other family members in their relationship? Tract housing offers no such places.

Ira Levin’s 1972 novel The Stepford Wives, made into a film in 1975, takes the uniformity of suburbia to its logical conclusion – if all the houses are the same, why not all the people? His sour, satirical take has housewives killed and replaced by compliant robots.

Spielberg isn’t unaware of suburbia’s downsides. As Roy Neary has his breakdown in Close Encounters, for example, the neighbours gather to watch, gawping from their driveways or leaning out of bedroom windows. When he speaks to them – ‘Good morning!’ – they ignore him. These people are crammed together and yet miles apart. But, overall, his take on suburbia is fond.

Spielberg himself grew up in just such a post-war neighbourhood, in Phoenix, Arizona. Joseph McBride made the pilgrimage while researching his 1997 biography of the director:

When a visitor enters Steven’s old neighborhood in Phoenix today, with its 1950s-era ranch houses still lining a broad, tranquil street crisscrossed by friendly kids riding bicycles, the feeling is inescapable: You’re not only going back in time, you’re entering a Spielberg movie.

Nowadays, anyone can visit Spielberg’s childhood home at 3443 North 49th Street thanks to Google Street View and to do so is startling – McBride is absolutely right, and it’s easy to imagine Spielberg location hunting, always seeking somewhere that felt just like home. Whereas others of his generation rejected suburban upbringings and wrote songs or novels mocking square life, Spielberg apparently yearned for it.

The two films in which Spielburbia really comes into focus are both from 1982: E.T. the Extra Terrestrial, directed by Spielberg, and Poltergeist, which he wrote and produced.

E.T. takes the growing list of tropes – or tics, perhaps – from Jaws and Close Encounters and amplifies them. For example, Spielburbia is defined by an abundance of mass-produced toys. In Close Encounters, Roy Neary tinkers with a model train set while a music-box in the shape of Pinnochio plays ‘When You Wish Upon a Star’. By the time we get to E.T., however, with the action playing out primarily in an eleven-year-old’s bedroom, there are moments when it feels like a commercial. ‘This is Greedo,’ says Elliot, showing his friend from outer space his Star Wars figures, ‘and then this is Hammerhead. See, this is Walrus Man. And this is Snaggletooth. And this is Lando Calrissian.’ A Texas Instruments Speak’n’Spell machine is even part of the contraption E.T. builds to ‘phone home’.

In E.T. we’re treated to sweeping crane shots of the suburb, filmed and set in the San Fernando Valley outside Los Angeles, and the majority of the action takes place there. Children on BMX bikes use their knowledge of the topography – its back alleys, broken fences and empty lots – to evade capture. Near the end of the film, a glimpse of a half-finished development on a new tract of land, into which the children escape, threatens to turn this into a film about the suburbs. Poltergeist, released in the same month of the same year, completes that journey.

The family man at the centre of Poltergeist, Steve Freeling (Craig T. Nelson), doesn’t just live in a suburb – he’s a salesman for the development company that built the bland but pleasant Cuesta Verde estate. Early in the film, director Tobe Hooper plays a sly trick, fading from a shot of the cluttered Freeling family kitchen to what looks like the same room stripped bare. Then Steve walks in with a couple who are considering buying what turns out to be a different house. ‘l can’t tell one house from the other,’ says the potential buyer.

At first, Cuesta Verde seems almost perfect, with all the Spielburbian signifiers. Then its flaws become apparent – the houses are crammed so close together that the Nearys and their neighbours keep switching the channels on each other’s TVs. As the haunting begins we learn that the truth is grimmer yet: the land on which the houses were built was a former cemetery and though the headstones were moved, the corpses were left in place beneath backyards and porches.

Perhaps this is the moment where Spielberg soured on Spielburbia, or at least moved on. He would not himself direct or write any more films with this setting, leaving his disciples to carry the baton.

If 1982 had the ‘Summer of Spielberg’, 1985 was the summer of Spielburbia, seeing the release of four notable films in the sub-genre.

Back to the Future was written by Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale and directed by Zemeckis, with Spielberg in the producer’s seat. Like Poltergeist, it offers a critical portrayal of the suburbs, taking advantage of the time travel plot to show a post-war Californian development, Lyon Estates, in both its well-worn 1980s incarnation and as a mere aspiration in 1955. ‘Live in the home of tomorrow…. Today!’ reads an advertising hoarding outside gates which open onto a tract of dusty land that is naked but ready.

The Goonies, directed by Richard Donner and based on a story by Spielberg, who also hovered around the set. It takes elements of E.T. – the child’s-eye view, the pursuit by sinister adults – and fuses it with the skeletons, subterranean tunnels and treasures of the Indiana Jones movies.

Neither Explorers, directed by Spielberg protege Joe Dante, or D.A.R.Y.L, had any involvement from the man himself, but both took components of Close Encounters and E.T., shook them up and glued them back together.

Even after 1985, the films kept coming – Flight of the Navigator and The Boy Who Could Fly from 1986, for example – but Spielburbia began to feel like a cliche and the movies like ever-weaker echoes.

Then, in 1989, Joe Dante directed The ‘Burbs, which might be said to put a neat full stop on this first phase. Dante’s films always walk a fine line between sincerity and satire and The ‘Burbs, which features Tom Hanks in an early outing for his ‘America’s Dad’ persona, tackles the strangeness of the suburbs head on while also celebrating them. Unlike Spielberg’s own suburban-set fantasies, which used real streets in real towns, The ‘Burbs was filmed on the backlot at Universal Studios. It used a set known as ‘Colonial Street’ which you will have seen in hundreds of TV shows and films – The Munsters lived there, as did the Desperate Housewives.

For twenty years or so after The ‘Burbs, Spielburbia was more or less neglected on film, even if a generation of us homesick for it, and for the comfort of childhood, drifted back there when the opportunity arose. Then in 2011 one of those children, director J.J. Abrams, revived Spielburbia in his own film, Super 8. Set in Ohio in 1979, it takes the masterlist of tropes and ticks them off one by one as a band of plucky kids on bikes take on both aliens and the military-industrial complex. It kicked off a run of similarly self-conscious homages including, most notably, the Duffer Brothers’ Netflix-produced Stranger Things, now approaching its fourth season, as well as a distinctly Spielburbian take on Stephen King’s scary clown story IT spread across two films.

What are people yearning for when they watch these films and TV shows? For some of us, it’s straightforward nostalgia for the pop culture we consumed as kids. For others – those who grew up in Ronald Reagan’s America – it must be a fond memory of a time when things felt less complicated.

And, dare I say it, Spielburbia is terribly, unashamedly white. Not only are there no black neighbours but scarcely anyone not presented as Anglo-Saxon or Irish. The first Levittowns were explicitly racist, with contracts stipulating that only members of ‘the caucasian race’ were allowed to buy or let. Spielberg, who often describes himself as having been the only Jew in his neighbourhood as a child, even turned Jewish actor Richard Dreyfuss into Roy Neary, apparently an Irish-American. It’s a dream of the 1980s as the 1960s or 1950s – a continuation of the American Graffiti tendency of Spielberg’s friend and frequent collaborator George Lucas.

More than anything, though, Spielburbia is a mood. Whatever outlandish events might be occurring, thanks to Industrial Light & Magic or the devil or visitors from space, as viewers, we’re invited to remember the best moments of being eleven years old. We’re reminded of sharing meals with our imperfect parents, around cluttered tables, knowing that there were toys to be played with upstairs and outside, in the golden light of the evening, streets to roam. Whether it’s Muncie, Indiana, or Bridgwater, Somerset, or a muddling of the two in memory, the feeling is real.

This piece originally appeared in the ‘zine The Happy Place published by the Bristol Writers’ Group in June 2020. You can still get paper copies. Our next ‘zine, Stepping Out, is due imminently and we’ll be performing new pieces as part of the Bristol Festival of Literature on 21 October. Get a ticket here.

When I moved to Bristol last year I wanted to get to know its culture and so asked around for tips on which novels and films best represent the city. Some People was one of the suggestions and after a little hunting I found a DVD released by Network in 2013.

It was lying on the coffee table when my then 69-year-old Dad visited and he recoiled at the sight.

“Is that… Is that Some People?”

“Yes. Why?”

“Oh, nothing,” he replied, still eyeing it with suspicion, and I knew there was a story to tell.

His reaction prompted me to watch the film sooner rather than later.

It was directed by Clive Donner who would make a name for himself with The Caretaker in 1963 and then head to Hollywood to make What’s New Pussycat? In 1965.

While Some People is clearly the work of a director finding his feet it is nonetheless an enjoyable drama about a teenager, Johnnie, played with charm and intensity by Ray Brooks, and his struggle to choose between straightening up or continuing a descent into delinquency.

Johnnie and his friends Bill (David Andrews) and Bert – a baby-faced David Hemmings – get into trouble racing their motorbikes along the Portway on the banks of the Avon and are banned from riding them which leaves them frustrated and deepens their boredom.

Then one night, while messing around in a church they’ve all but broken into, they are taken under the wing of Mr Smith, a local youth group organiser played by veteran British actor Kenneth More, who encourages them to form a pop group.

Bill rejects Mr Smith’s mentorship seeing in it an attempt to control him and breaks with Johnnie and Bert, falling in with a gang of hard-cases.

Then, fuelled by jealousy over his girlfriend’s attraction to Johnnie, Bill tries to sabotage his friend’s new found stability. It’s small stuff – squabbling and scrapping, hardly Marlon Brando territory – but that makes it feel all the more authentically British.

The film’s strengths are its cast, setting and its considerable charge of nostalgia.

Filmed entirely on location, it captures the reality of Bristol in the heat of post-Blitz reconstruction, half tumbledown harbour city, half planners’ dream.

A large part of the action takes place on the Lockleaze estate, high on windswept Purdown in the city’s northern suburbs.

St Mary Magdalene with St Francis church is one of the stars of the production – a mad modernist vision in concrete and stained glass that provides a surreal sci-fi backdrop to the boys’ antics. The church opened in 1956 and was typical of the space age houses of worship built on overspill estates all over the country in the post-war period.

Unfortunately, though it looked astonishing, it was plagued with structural problems and was demolished in 1994, which only adds to the value Some People holds as a record of a time and place.

Another particularly striking scene takes place in the Palace Hotel, an especially grand Victorian pub on Old Market. There Johnnie has a breakthrough conversation with his taciturn working class father played by Harry H. Corbett (whose Bristol accent, it must be said, ends up drifting to somewhere near Cork). Real pubs are rarely seen on film, especially in colour, and this is a particular lovely example – cast iron tables, a beaten up piano, everything dark with age, the aroma of smoke and stale beer positively wafting from the screen.

Those with an interest in public transport will thrill at the plentiful footage of the famous Bristol ‘Lodekka’ buses while aviation geeks will get a similar thrill from scenes of Mr Smith at work: when he isn’t encouraging young tearaways to play nicely together he is an engineer overseeing test flights of the Bristol 188 ‘Flaming Pencil’ supersonic jet.

Anneke Wills plays Mr Smith’s daughter, Anne, who has a teenage fling with Johnnie. His influence leads her to buy tight jeans which she further shrinks to fit in the bath. You’d think this scene a little ripe if it turned up in a modern period drama set in the 1960s but here it is charmingly authentic.

In general the film is a useful reminder that in 1962 kids were still wearing quiffs and leather jackets.

Passing scenes of dancehalls, espresso bars and roadside motorbike hangouts will also bring back memories for anyone who was on the scene in the 1960s. Less thrilling but no less evocative are the bus stations, council houses and cigarette factories where real life plays out between bouts of fun or violence. It isn’t Grim Out West, only a little grey, a little sparse, slow and sleepy.

If Some People has weaknesses they are the score – square rock’n’roll arranged by Ron Grainer and performed by local Shadows wannabes The Eagles – and the fact that it is effectively propaganda for the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Scheme which part-funded the production. I say ‘effectively’ because Bill, the rebel, delivers several stinging diatribes against it and, frankly, seems much cooler than Johnnie and his gang of goody-goodies.

Once I’d finally watched the film I was more curious than ever about Dad’s reaction and pressed him on it when we next went for a pint. With some reluctance he told me the story.

Like Johnnie, Bill and Bert, he and his 14-year-old friends on a Somerset council estate were often bored and got up to mischief. When it wasn’t joyriding, it was repeatedly breaking into the local CO-OP to steal cigarettes.

One night he returned home to find his father in a foul temper.

“Where have you been, boy?”

“In town to see Some People.”

“Oh, yeah? Some People? Well while you’ve been out, some bloody people have been here to see you.”

The people in this case were the police and Dad ended up with a criminal record.

After that, like Johnnie in the film, he started a rock group and threw his energy into making music rather than trouble, before settling down to a life working in factories and warehouses.

Art imitating life imitating art.

Too often fictional portrayals of small towns and villages lean on the twee – the heirloom plate version of the England What We Have Lost, where Miss Marple ever knits socks for the eternal Home Guard unit that will return one day aboard a steam train when our country needs it most. But Detectorists and This Country both recognise a space between town and country where people live and work without necessarily thinking of their lives as ‘rural’, and without nostalgia.

The world of Mackenzie Crook’s Detectorists is gentle and idealised, but not by much. People have jobs cleaning motorway verges, polishing hospital floors, packing and dispatching vegetables; they struggle for money; they live in red-brick houses or flats above shops, not cottages or farmhouses. The pubs look like real pubs, where people more often drink lager than the ale prescribed by lore. Yes, the countryside is beautiful, and filmed beautifully, but it is also full of cars, vans, litter (“Ringpull… ’83… Tizer.”) and infrastructure. It looks free and open viewed from the right angle but is actually carved up by invisible lines into ‘permissions’, not only a human landscape but one that has been that way for thousands of years, filled with the debris of a million past lives.

If there’s a ‘but’ with This Country it’s the sense that the writers are chuckling at ‘chavs’, turning out a form of prole porn. I’m very sensitive to this as the bearer of a working class shoulder chip sufficiently hefty that it causes me to walk in circles if I don’t compensate but, on the whole, I credit Daisy May and Charlie Cooper, who write and star in the series, as acute observers rather than sneerers. Kerry and Kurtan Mucklowe live in the kind of plain post-war council houses of pre-cast reinforced concrete that you’ll find in every town and village the length of England, and any hint of the bucolic is undercut by the sight of pylons and motorways in the background. There are moments when I think, hold on, wasn’t I walking down that street last week? Didn’t my aunt and uncle live in that house?

Both shows depict ordinary people with ordinary un-town accents having complex relationships, deep feelings, and pursuing strange obsessions. If you think Kurtan taking the scarecrow competition deadly seriously is far-fetched then you don’t know Bridgwater Carnival. An obsessive detectorist would have fit in well on the estate where I grew up among the scooter fetishists, boat restorers, woodworkers, quilt-makers, Hammond organists, gooseberry growers and CB radio enthusiasts. Even the cool boys from school would gather in the playground to peruse catalogues of angling equipment.

I have a bias towards the south and the rural, of course, but I might just as well have mentioned Car Share, created by Paul Coleman and Tim Reid and brought to life by Peter Kay. It depicts an only slightly heightened vision of the suburbs, retail parks, ring-roads and roundabouts where so many people live lives nonetheless full of feeling.

If this is a golden age for British programmes about ‘boring people doing boring things’, as John Lennon once said in dismissal of Paul McCartney’s social realist songs, then it might be just what we need at a time when it feels as if half the country doesn’t know or much like the other, and when the question of what it means to be English has once again become so grimly present.