Alan ‘Ginge’ Newman has died at the age of 75 after a lifetime of making and thinking about music.

He wasn’t a full-time musician, however, because like most people he had to work to support his family – that is, my mum, Eileen, my brother, Tim, and me. That he found time to pursue creative interests around night shifts, factory work, warehouse work, and even a stint digging graves, suggests just how strongly that flame burned.

He was born in 1948 at Woolavington on the Somerset Levels to Agnes and Ernest Newman, East Londoners who moved west for military service and war work and never went back. Alan loved Somerset, spoke with a wonderfully warm local accent, and flew a Somerset flag in his back garden until the day he died. Nonetheless, he felt those London roots, which manifested in an occasional imitation of his father shouting “Gertcha!” (via Chas & Dave) and his support for Arsenal.

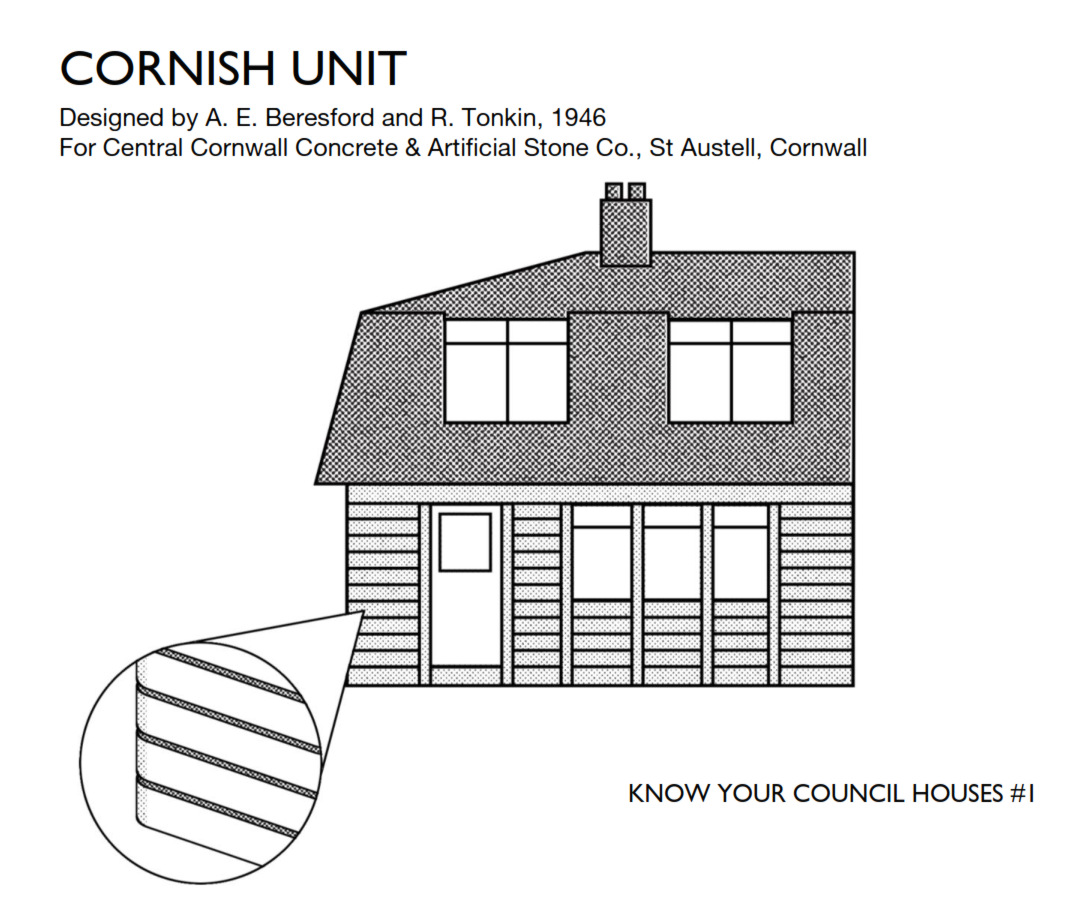

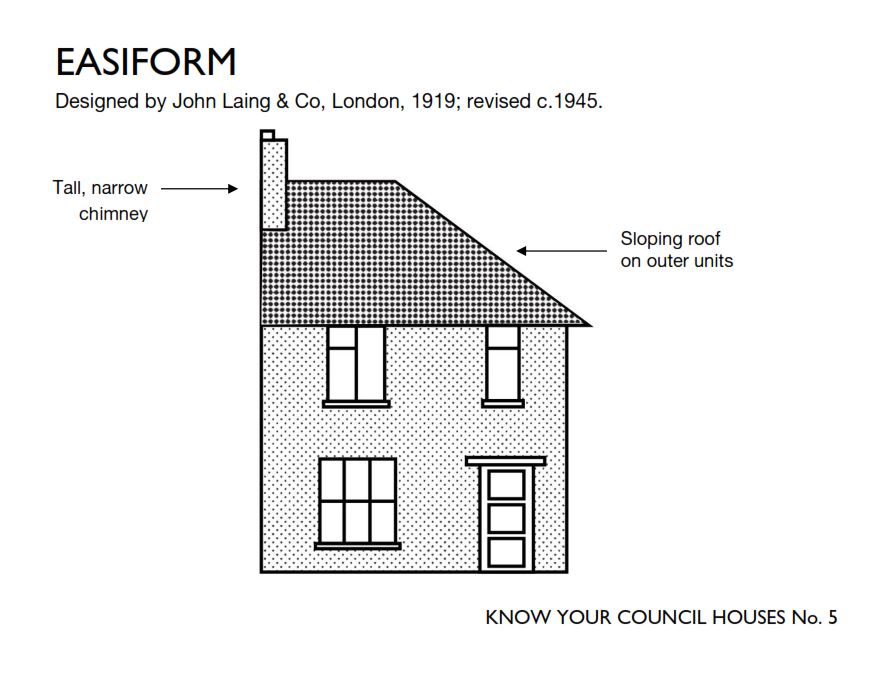

His childhood was difficult in various ways. First, there was poverty. The Newmans lived throughout the 1950s in a rickety prefabricated house on a council estate appended to a village. He later recalled shivering beneath an Army greatcoat in an unheated bedroom with ice on the windows and he was utterly baffled by nostalgia for prefabs and post-war Britain.

Secondly, there was illness. Not expected to survive longer than a few minutes, he was named quickly by a nurse who borrowed his mother’s initials (Agnes Kathleen) to conjure up Alan Keith. He lived but thereafter spent months in hospital, and years in and out, with an undiagnosed respiratory condition.

Thirdly, there was the challenge of growing up in a family ruled over by a heavy-drinking, gambling, womanising bully whose time in the Royal Navy did nothing to sweeten his manners or temper.

It’s perhaps no wonder that Alan was an unruly child and teenager who drank his first pint of beer in a pub at the age of 12. Though ashamed of it for much of his life he spoke more openly in recent years about his adventures in joyriding and his juvenile criminal record for breaking into the village shop to steal cigarettes. In fact, one of his favourite stories was about returning from a screening of the 1962 film Some People at the Palace Cinema in Bridgwater to find his father furious after a visit from the police.

“Where have you been, boy?”

“In town to see Some People.”

“Oh, yeah? Some People? Well while you’ve been out, some bloody people have been here to see you.”

Though a scholar in his own way – more on that later – Alan didn’t enjoy school and was happier playing sports or, more often, mucking around with a gang of friends. He left Sydenham, the brand new comprehensive in Bridgwater at 15, with no qualifications and went straight into the world of work, where he would remain for 50 years.

He trained as an apprentice coachbuilder for a while, then became part of a demolition crew for Pollard’s of Bridgwater. “If you wanted something smashing with sledgehammers,” he later recalled, “you called the Newman boys.” There was also a stint in the Army which, to his great disappointment, was cut short because he failed a medical examination. (Or perhaps, as he once suggested, because he joined the Young Communist League hoping to meet liberated women, which wasn’t the done thing for people serving in the armed forces during the Cold War.)

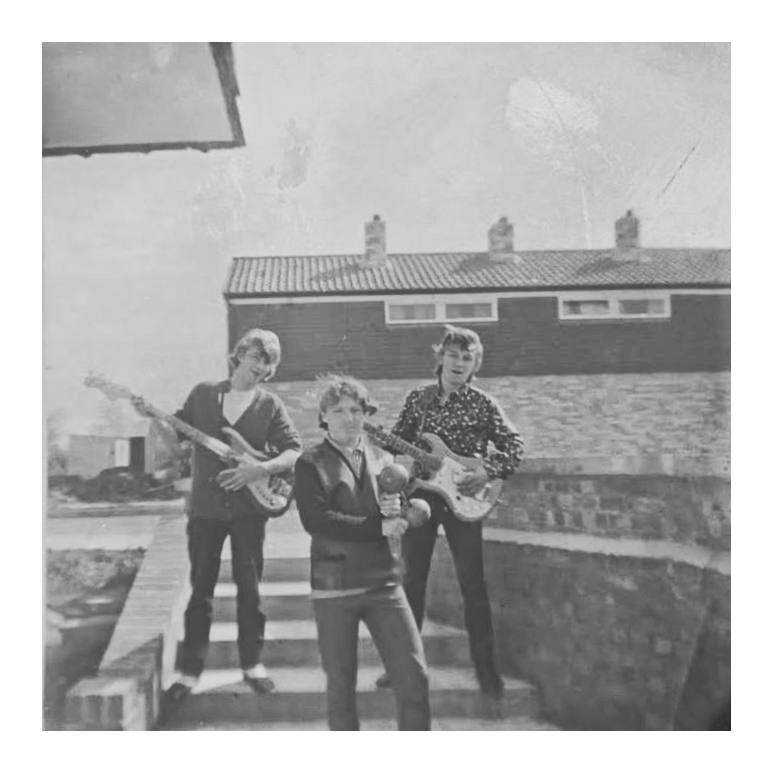

Like many teenagers in the 1960s he also developed an interest in rock’n’roll music and formed a succession of bands. Under a pseudonym he was lead singer and leader of Ginger Ellis & the Dracos. Later, in red velvet flares during the psychedelic era, he fulfilled the same role in The Keystone Kops, who even cut a single with ‘Can’t Stand No More’ on the A-side and ‘The Rise and Fall of a Persian Pig in E-Minor’ on the flip. Alan’s favourite band was The Rolling Stones whose first two albums, filled with R&B, rock’n’roll and blues covers, would form the template for his musical taste for decades to come.

Alan and Eileen met in 1970 in a Bridgwater pub on a busy Saturday night. He was 21, she was 17, and they were engaged by the following Thursday. They married in 1971. Drifting away from his own family he found a warm welcome from Eileen’s parents and the four of them became drinking buddies, chain smoking cigarettes, and playing the four-player card game euchre as they crawled the pubs of St John Street, Eastover, and into town.

Though he continued to buy and play records, loudly, he had less time to make music as he settled into a steady job at British Cellophane. Wading in troughs of solvent without adequate protection no doubt did some lasting damage but, at the time, he was simply happy to be bringing home the kind of money that paid for a house, a car, and a decent quality of life.

It was difficult to have children and took longer than expected. A secret Alan and Eileen kept for decades was that they ended up using the then pioneering technique of donor insemination (DI) via Dr Margaret Jackson’s clinic in Devon. Perhaps he felt embarrassed about this, or felt it to be a failing on his part, but as far as my brother and I are concerned, it shows the sheer generosity of his spirit. He suggested this because Eileen needed it, and committed fully to the experiment. And he was never less than doting as a father, and never gave us the slightest reason to doubt he loved us – which is not always the experience of people conceived through DI. When we learned the truth many years later, Alan’s first concern was whether it changed anything in his relationship with his sons. We were able to tell him that not only had nothing changed but, if anything, we respected and loved him all the more.

In the 1980s, Alan and Eileen took on a decrepit Whitbread pub in Exeter which they ran for several years. Alan had a real talent for engaging with customers and creating a sense of community. His turn as Widow Twankee in the pub pantomime was a surprising success, again revealing an instinct for creativity and performance at odds with his macho persona. Unfortunately, it is and always has been tough to make a living in a tied public house, and the experience bankrupted them.

Alan hated to be unemployed and resented living in a council house, which became necessary in the aftermath. It was in this low period that his dormant interest in blues music resurfaced – perhaps because he was now feeling it in his heart. He acquired a cheap electric guitar, a Gibson Les Paul copy, and tried to learn to play. When that didn’t work, he switched to the bass guitar and realised he had found his instrument. Our house began to throb to the sound of walking 12-bar patterns, or the sparse moodiness of the bass part for ‘Stormy Monday’.

Working long night shifts plus overtime operating a lathe at Wellworthy’s in Bridgwater he had little time and even less energy. Blues bands would form around him, rehearse for a while, then break apart. All the time he kept listening to blues music, reading about blues music, and lecturing anyone who would listen about the career of Muddy Waters, or chord progressions, or the meaning of the obtuse lyrics of 1930s acoustic blues songs. What is a peach-tree man? Alan could tell you. The house was filled with books such as Paul Oliver’s The Devil’s Music. He was often to be seen in the crowd at gigs in Bridgwater, Taunton and further afield, at a time when blues music was a staple part of the offer at pubs and social clubs across Somerset.

As a performer, things finally came together at around the turn of the millennium when Alan met his great friend Les Leiper and they formed the band Witch Doctor. At last, he was part of an efficient gigging band that played most weekends in pubs across the region, with the thump-thump-thump of Alan’s bass providing a steady clock. His proudest achievement was playing multiple gigs at The Old Duke in Bristol, a legendary jazz and blues venue where he’d previously seen some of his own favourite bands perform. When Alan eventually left Witch Doctor it was partly because, being a man of his time, he was unable to express his frustrations in words. Quitting was the easier option.

In the years that followed, he joined or formed many more blues bands, each one with its own unique style and set list. The Blue Healers, for example, gigged in Bristol and elsewhere. Alan’s problem was that he wanted to play blues music, and nothing but blues music, and, inevitably, most bands would start to talk about adding soul or classic rock tunes to the set. ‘Mustang Sally’, though a fine song, did not belong in the repertoire of a blues band. Nor did ‘Sweet Home Alabama’. Again, although he got better at having these conversations, he would often simply leave rather than deal with conflict or awkwardness.

Alan retired from his final job as a warehouseman at 67. He’d been doing heavy, physical work for most of his life, and his body had begun to creak. His lungs, never quite 100% functional, began to fail him and he was diagnosed with both asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). You can’t help but wonder about all those jobs – demolition in the era of asbestos, factory work with baths of solvents – and the cold dampness of his childhood home. Still, in retirement, with two beloved dogs, he started to get fit, rambling with Eileen over the Mendips and across the Levels.

Both being village kids, at heart, they moved to the country, settling in Rooks Bridge. He would stand and stare at the landscape, listen to the birds, and relish the fresh air. His bands sometimes rehearsed in a nearby stable, or in the kitchen at the house, and the neighbours would turn off their TVs to listen.

During the pandemic his lung conditions put him in a high risk category and was effectively trapped in the house for several months. This did him no good and he emerged from successive lockdowns seeming suddenly much older and far less robust. A chest infection in 2023 never quite cleared and dragged him down for over a year. Finally, in August 2024, it got him. He died while receiving care at Weston General Hospital, not long before dawn.

That urge to make music, and to create, was with him until the end. Shortly before he went to hospital for this final stay, he started talking about recording a podcast, and also snuck an advert onto Facebook when Eileen wasn’t looking: did anyone want to form a blues band for some low key rehearsals?

Alan Newman, born November 1948, died August 2024.