What happens when angry young men are more than angry? These three roughly contemporary books give us portraits of youths struggling with their own murderous instincts.

I came to The Furnished Room, Big Man and The Dead Beat one at a time after finding tatty old paperbacks in charity shops or roadside book swap boxes.

All three were written during a period of anxiety about juvenile delinquency and a simultaneous growth in popular discussion of psychopathy.

The term ‘psychopath’ was popularised in the 1940s and a slew of novels and movies from that point on portrayed a particularly chilling type of killer. Being outwardly in control, and even charming, they were able to walk and live among us.

Joseph Cotten’s Uncle Charlie in Alfred Hitchcock’s brilliant 1943 film Shadow of a Doubt is one example. Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr Ripley introduced us to the chameleonic Tom Ripley in 1955.

At the same time, young people were beginning to seem dangerously out of control, with motorbikes, switchblades, and a lack of respect for authority.

That’s the context in which the following three pulp paperbacks emerged.

Little boys to broken men

Big Man is the earliest, published in 1959. Its author was prolific novelist Evan Hunter, born Salvatore Lombino, and best known for a series of police procedural novels written under the name Ed McBain. He wrote this book as Richard Marsten and it reflects something of that sense of fractured personae.

It’s written from the point of view of Frankie, a young man living in poverty with an alcoholic mother, and drawn into petty crime by sheer boredom. Petty crime leads to organised crime where, after resisting, he embraces his true murderous self.

The 87th Precinct novels are set in an anonymised fantasy of New York where Manhattan is Isola, Queens is Bethtown, the river is the Harb, and so on. Big Man is set in New York proper, where Hunter grew up and which he knew at street level.

This authenticity shines through in his portrayal of the everyday lives of idle young men with no coin in their pockets and every reason to feel detached from the world. That Frankie’s best friend Jobbo has appalling body odour sets the tone: this is a world where sweat stinks.

These early chapters are similar in mood to The Incident, a 1967 film based on a 1963 TV play, about two young men who terrorise a New York City subway car. In both cases, the thesis is that the road to murder begins at robbery, and robbery comes as much from a need for something to do as from the urge to acquire.

For Frankie, the lure of organised crime isn’t so much money but also a sense of family, respect, and affection. The mob boss is a father figure – someone who tells Frankie he is a good boy and has value.

Even through Frankie’s unreliable narration we see, of course, that he is being preyed upon and manipulated. Through favours owed, debts incurred, steps taken from which there is no walking back, he is drawn away from society and becomes ever more tangled in a shadow world with its own values.

What really sets the book apart is Frankie’s relationship with his two lovers. Frankie is torn between two women – a sexually insatiable gangster’s moll who has been with the whole crew, and the nice neighbourhood girl who wants to start a family.

It is shocking when he shoots the former on the indirect order of his boss. It is absolutely devastating when he puts a bullet in the head of the second because she has become a hindrance to his career.

Hunter plays with our prejudices: promiscuous girls who get involved with criminals put themselves in the firing line, but nice girls who just want their boys to go straight? They deserve a happy ending.

By the end of the novel, Frankie has become a killing machine, like a soldier trained for combat. He follows orders and shoots when he’s told to shoot.

He is also cursed with the knowledge that if he can bring death to the others so swiftly and easily, then death can come to him the same way.

The killer is in the house

Robert Bloch’s The Dead Beat was published in 1960 and tells the story of another blank, murderous young man.

Larry Fox is a dead beat jazz pianist who finds a way to break out of the world of crime, prostitution and drugs and into the nice suburban home of a nice suburban family.

His great skill is being able to present as a good boy when it suits him – or maybe these are actually glimpses of the real Larry, or another Larry, battling Bad Larry for supremacy?

As Good Larry, he’s bashful, well-spoken and polite. He’s musically talented and has hopes to study composition at university. This is catnip for the middle class saviours who take him in and nurse him when they find him unconscious in the back of their car. Especially the women.

But Bad Larry plans to get revenge on his former accomplices in a robbery and will fuck, rob, drug and manipulate anyone who gets in his way, or can help him achieve his goal.

Bloch doesn’t expect the reader to read between the lines. He has his characters debate matters of juvenile delinquency and ‘the beatnik problem’ which gives him an excuse to insert chunks of his thesis into the text:

It all began with World War One, I suppose. Up until then, the traditional role of the young man in this country was that of an apprentice. In rural communities he started as a hired hand or helped his father on the farm. In the cities he entered business as a clerk or a messenger or an office boy. Youth accepted a subordinate position unquestioningly, even when the industrial era developed… War is the great glorifier of youth… Our economic leaders, through the media of advertising, assure us that it is the duty of everyone to appear young; to buy products which enhance the illusion of immaturity. Our books, magazines, motion pictures and television programs inform us, not too subtly, that romance and adventure are the exclusive property of young people between the ages of seventeen and twenty-five. Nobody over that age ever falls in love or experiences anything of lasting significance, except for a few oddball characters thrown in for comedy relief.

Bloch was primarily a writer of horror stories and the scary idea in this story is that adults cannot tell good boys from bad ones. That nice young man your daughter is dating might be a hophead, a junkie, a pervert or a killer – better not let him in. Especially not if he reminds your wife of when she was young.

The kitchen sink killer

Crossing the Atlantic, Laura Del-Rivo’s The Furnished Room was published in 1961 and filmed as West 11 in 1963.

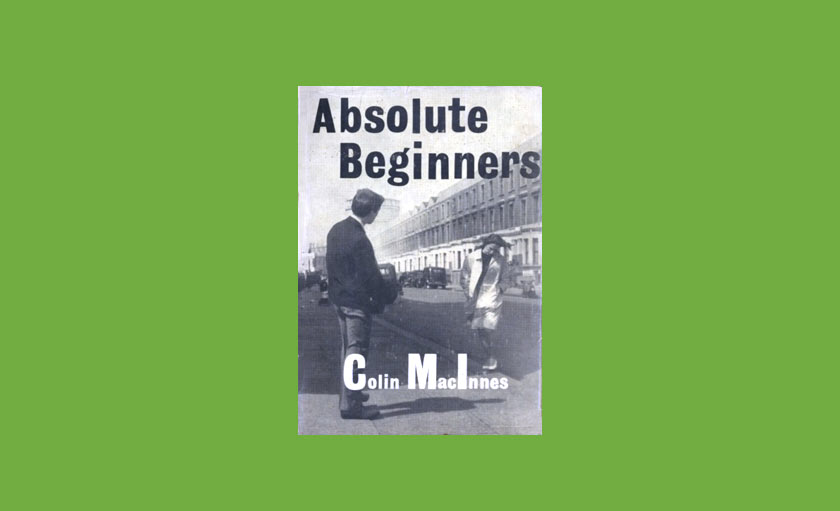

In many ways it sits alongside British social realist novels like Saturday Night and Sunday Morning or, closer in tone and setting, Absolute Beginners. The difference is that Del-Rivo introduces a gun into the mix turning it into something like a crime novel, or one of Georges Simenon’s romans durs.

Joe Beckett is another semi-intellectual, but a reader rather than a musician. Like Larry Fox, he is capable of making himself presentable, as long as nobody gets close enough to notice the grubbiness of his shirt or smell his unwashed socks. To some people he reads as clever, almost an intellectual, although his drug-fuelled lectures don’t stand up to the scrutiny of really intelligent people.

As with the protagonists of many other British novels of the period, he is too full of fury to be constrained by the drudgery of a nine to five job, or by love and marriage. Unlike Arthur Seaton, however, he decides that committing a murder might fix the emptiness inside him.

Haunting the cafes and bedsits of West London, Joe meets a classic British type: the faux-military conman with a range of regimental ties to suit whichever story he is telling on any given day. Keen to inherit from an aged aunt, he draws Joe into a scheme apparently inspired by Strangers on a Train.

That standard crime plot isn’t where the excitement lies in this story, though. That’s in Joe’s battle with his own worst instincts. He has constant intrusive psychopathic, paedophilic and fascistic fantasies. Reading about Nazi concentration camps thrills him:

Beckett’s immediate reaction had been a burst of sadistic joy. He knew that if, at that precise moment, he had seen a woman prisoner with her arms yearning for a lost child, he would have kicked her in the face. The shooting of the new detachment had pleased his sense of order. They were damn nuisances, screaming and panicking like that. Shooting them was the only orderly thing to do. He loathed the prisoners for their ugliness, their suffering, and their lack of pride. The photographs of these degraded sufferers, squatting behind their barbed wire, had revolted him so much that he had thought it a pity that the whole lot hadn’t been gassed. He had preferred the photographs of the Nazi guards, who had at least looked clean and self-respecting.

This book in particular feels like a commentary on present day alt-right, manosphere and incel cultures.

All three books force us to inhabit the minds of boys who don’t know how to love, even if they sometimes get close.

Those are the moments when we want them to break through the barriers, to untangle the complex feelings that threaten to break through their anger, resentment and hatred.

But they can’t do it. So they reach for guns and point them at innocent people.