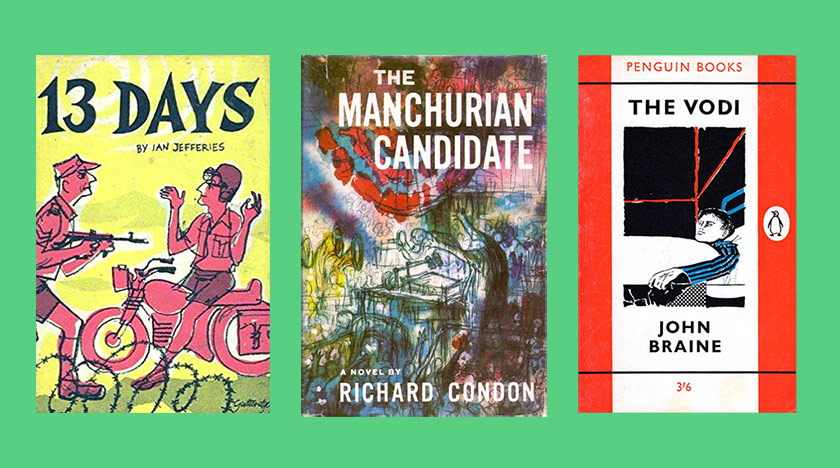

The three most recent books in my #reading1959 project were Thirteen Days by Ian Jefferies,The Manchurian Candidate by Richard Condon, and The Vodi by John Braine. They fit together oddly well.

One common theme emerging in many of the books from 1959 I’ve read this year is the legacy of war – PTSD, institutionalisation, lives arrested or derailed, and a sense of the world recovering from a nervous breakdown.

The Manchurian Candidate takes the Korean War as its starting point, telling a wonderfully compelling story of paranoia and brainwashing. The 1962 film is better known than the book and perhaps rightly so: the book was essentially written as a movie pitch and is far less subtle or convincing. In fact, it’s positively baroque.

Sergeant Raymond Shaw is an unlikable man, unpopular with his platoon. He is identified by a Chinese-Soviet brainwashing project as the perfect candidate to be programmed as an assassin, not least because of his privileged upbringing as the stepson of a rapidly rising American politician.

The early chapters, set in Korea and depicting the brainwashing in progress, are the best. Shaw’s cold-blooded murder of his comrades, under hypnosis and in front of an audience of Communist dignitaries, is chilling.

There’s also something grimly fascinating in Shaw’s uneasy friendship with his former commanding officer, Ben Marco, each having been forced to like the other through hypnotism. There’s material enough there for an entire extra novel.

Shaw’s mother is the other standout character – a controlling, social climbing psychopath who nailed a puppy’s feet to the floor as a child and maintains her perky attitude with shots of heroin between embassy balls. She both uses her son for political gain – the Chinese fix it so that he is awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, making him a valuable PR tool – and (just when you think it can’t ramp any higher) seduces him while he’s hypnotised.

What makes the book difficult to enjoy in 2019 is exactly that hysterical, over-the-top tone, which carries through into the writing style. It’s part wannabe beat prose, part Mickey Spillane, all pure ham:

There is an immutable phrase at large in the languages of the world that places fabulous ransom on every word in it: The love of a good woman. It means what it says and no matter what the perspective of or stains of the person who speaks it, the phrase defies devaluing. The bitter and the kind can chase each other around it, this mulberry bush of truth and consequence, and the kind may convert the bitter and the biter may emasculate the kind but neither can change its meaning because the love of a good woman does not give way to arbitrage.

The typically pulpy attitude to women doesn’t help, either. We’re supposed to like Marco and root for him, for example, but he uses women and even occasionally hits them if they won’t do what he wants, the latter being presented as evidence of his impressive virility. No thanks. Otherwise, women are mad bitches (see above), sexy angels (Marco’s fiance) or plot devices to move forward the stories of Important and Vigorous Men.

***

Thirteen Days (or 13 Days in some printings) is also about foreign wars and the madness they encourage in otherwise ordinary men.

Set in Palestine in 1948, it presents another Sergeant, Sergeant Craig of the Royal Engineers, who has embraced the chaos and corruption of the Middle East and lives a maverick life of arms smuggling and artful skiving.

A characteristic moment is his admission that, building a vital water storage tank for a far-flung British Army base, he made up for a lack of concrete by using boulders in the foundations, only because of a lack of boulders he actually used dead donkeys: “What with the heat and everything they must have swelled. But anyway, the foundations cracked…”

Something about him brings to mind Len Deighton’s unnamed insubordinate spy, christened Harry Palmer on film, but Craig also has something in common with the protagonist of Absolute Beginners – a young man who’s not quite as hard or impervious as he likes to think.

When idealism surfaces, unexpectedly, he becomes allied to the Jewish cause, falls in love with a beautiful young woman who works as a driver for a paramilitary group and ultimately has his heart broken when all this proves to be more than a game.

The details of Army life and of the landscape are well drawn, clearly based on the author’s own first-hand experience (Ian Jefferies is a pseudonym), as is the sense of detachment and unreality triggered by being forced to live so far from home, with so little purpose.

Thirteen Days is an interesting book but hard to latch onto: is it supposed to satire, or a straight-up thriller? (Check out the cover, above, which suggests Doctor in the House.) It succeeds best when it settles on the latter and gives us a stretch of suspenseful action into the finale.

***

John Braine’s The Vodi is a peculiar and rather brilliant book, up to a point.

Dick Corvey is recovering from tuberculosis in a sanitarium in the north of England from where he reflects on his life and misfortunes, battling the onset of bitterness as much as TB.

Structurally, there are echoes of Free Fall, All in a Lifetime and No Love For Johnnie, with memory and The Now intermingled throughout.

What gives the book its interest is the bleakness of tone – the north here is all shadows, decay and drizzle – and, of course, the Vodi. The Vodi is an organised crime gang made up of goblin-like minions under the control of the monstrously fat Nelly. The Vodi controls the district, torturing and ruining the lives of its victims, primarily out of spite. There’s a hint of Arthur Machen in it but also of Cruella De Vil.

Dick and his best friend Tom invent the Vodi as boys but Dick persists in clinging to the idea as a luckless adult. A key moment in the book, the point at which Dick and Tom diverge, is when Tom disavows the existence of the Vodi immediately after his first sexual experience with a girl. Tom goes on to take control of his own destiny, embrace risk, and eventually finds success; Dick bounces from Army to clerical job to sanitarium to sanitarium job, passive and pathetic.

And that’s Braine’s argument, in the end: that you have to fight, strive and desire. Only when Dick falls in love with a nurse, Evelyn, do things change for him. Evelyn loves him but becomes engaged to another man because she can’t bring herself to shackle herself to a sad case like Dick. Tempted as he is to blame the Vodi and surrender, his passion for her prompts him to discover the inner resources he needs to overcome the disease and make the bold decisions necessary to become a full personality.

***

War, the maddening power of institutions, sinister controlling forces, the struggle to work out what being a man really means… As the final stretch of #reading1959 begins, a thesis is certainly beginning to form.

And though this wasn’t the plan when I started out, it’s all proving very handy for my current writing project, a crime novel based on a true story and set in the late 1950s. Surface detail is easy but I feel as if I’ve really got into the psychology of the time.