Christmas Day, four in the afternoon, and the stale air in the front room feels like a weighted blanket.

Dad is asleep in his grubby chair, whistling through his drooping white moustache. Mum is fussing about, back and forth from the kitchen, groaning every time she puts weight on her hips. My sister is staring at her phone, scrolling, liking, scrolling, liking…

We’re not allowed to watch TV because our family tradition is to play board games and card games, except that doesn’t happen any more, not since Aunt Jenny died and Uncle Terry stopped coming. Now, we just vegetate and compost.

Two more nights to go. Just two more nights.

‘I’m going for a walk,’ I say, surprising myself. ‘Get some air and the last of the light.’

And I’m coat on, out the door, before anyone can stop me.

It doesn’t feel much fresher outside. Like most Christmases, it’s grey and almost muggy.

One foot in front of the other, walking nowhere in particular.

I’ve lived away up in the city for twenty years and my home town feels psychedelically weird, like one of my stress nightmares. Is this really where I grew up? Are these really the streets I used to play on?

The pylons that run the length of the main road on the estate crackle as the evening dew begins to settle. I feel the hairs on my neck spring.

Nobody told me the pub was gone. There’s just a bare space now, surrounded by a wire fence, and notices about planning permission.

On the corner, there’s a phone box. One of the glass and steel type, skeletal and unromantic. It was where I used to call my first girlfriend during university holidays. I stop for a moment and look at the dangling handset. I wonder if it still works.

Then it rings.

There’s no traffic on the roads, no sound at all from the nearby houses, and the electronic chirruping seems outrageously loud. I feel embarrassed, as if I’ve made it happen, and quickly walk on. The phone keeps sounding behind me, calling after me even, but eventually fades out of range.

I take the next left, towards Holy Trinity Church and a patch of grass we used to call, charitably, The Green. That’s where Deano Tremlett broke my ankle playing football, with the ‘NO BALL GAMES’ sign for one goalpost and a cricket stump for the other.

I pass a shuttered cornershop, a shuttered fishing tackle shop, and a house lit up like a Las Vegas casino. An inflatable peeping tom Santa is staring through the window of the bedroom.

As I near The Green, I remember something: next to the post box and the concrete planters full of cigarette ends, there’s another phone box. I’m not exactly braced this time but I am ready. When it rings, though, I still say ‘Bloody hell!’ out loud.

Oh, I see. I get it. Someone’s watching me and they’re calling it from a mobile. It’s a prank. I smile for the benefit of my hidden audience and reach for the handset.

‘Hello?’ I say.

I’d forgotten how bad they smell, phone box handsets: bad breath, mould, metal. The black plastic feels cold in my hand.

The line crackles slightly.

‘Who is it?’

Then I hear something. Drums. A thin echoing beat, like hold music.

Now this makes more sense. It’s a robocall. Spam. I breathe out, relieved, and slam the handset back into place.

Keep walking. Past the church, up a rough path by the side – Hog Alley we called it as kids – and through into Chamberlain Court. Follow that towards the secondary school, the primary school and the health centre.

Through windows and net curtains I see families on sofas or in armchairs, staring towards the TV, either slumped or wrestling with game controllers.

I notice the phone box on the corner of Franklin Road well in advance. Its glass is stained and fogged. There’s grass growing around its base. I think about avoiding it but don’t want to turn back the way I came.

And of course it rings.

‘Fuck off,’ I shout at it.

The ringing, somehow, gets louder, so I have to answer it before anyone else comes along.

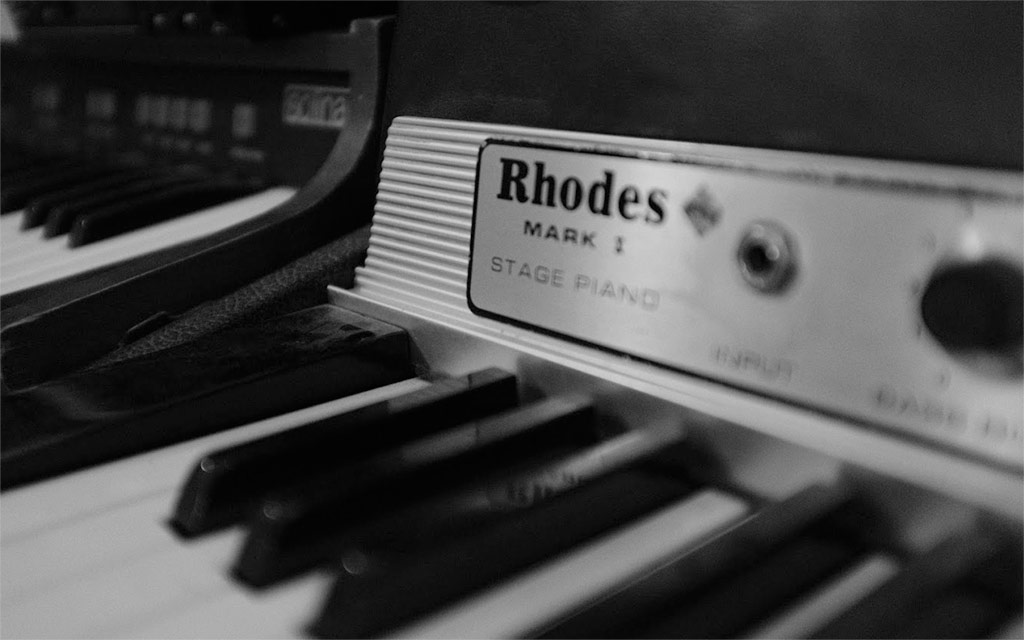

This time, the music starts immediately, before I have time to speak. This time, I recognise it.

It’s the intro to ‘Last Christmas’ by Wham! with its chugging synthesisers and a wordless vocal. George Michael’s voice squeezes through the small speaker as he sings the first line: ‘Laaaast Christmas…’

Then the recording catches.

It’s not quite like a record skipping but, rather, an insistent hard-edged loop.

‘Last Christmas/ Last Christmas/ Last Christmas/ Last Christmas/ Last Christmas/ Last Christmas/ Last Christmas/ Last Christmas–’

It’s the same few seconds of music but seems more intense with each repetition.

I drop the handset and leave it swinging as I walk away.

I can still hear the music for a few steps, dissolving into pure treble, then disappearing altogether.

It’s getting cold now and I need to be home where it’s safe. I break into a jog.

Each phone box I pass rings for me, desperate to tell me something.

I run up the garden path and turn my Yale key, the one I’ve had since I was fourteen.

In the kitchen, Mum and Dad are hobbling about the dining table, bickering over the pickled onions and the cheese board.

‘What’s the matter?’ asks Mum.

Clammy and shaky, I force a smile.

‘Nothing,’ I say. ‘Just glad to be here.’

And I mean it.

If you enjoyed this story then check out my collection Municipal Gothic which has thirteen stories about ghosts on council estates, devil dogs in supermarket car parks and haunted tower blocks.