The members of the Society of Particular Peculiarities meet every month, but the December meeting is the most important and best attended of the year, because that is when I tell my ghost story.

There was a good mist up as we gathered last week in the venerable old county town. The clubhouse is off the market square, old but not ancient, being a former Unitarian chapel of 1712, with a clamshell hood above the door, and a galleried interior. It is generally colder inside the clubhouse than outside but on the evening of our meeting Gough, the caretaker, had provided a paraffin heater and a supply of blankets.

Very nearly the entire membership of the Society was in attendance, including Mrs Neville, the celebrated lepidopterist, and the silent Sampson twins who had travelled all day on foot from their remote farmhouse. They were collectors and chroniclers of shipwrecks despite not having been within sight of the sea their whole lives, as far as I am aware.

When all were gathered in the pews, with hunting cups of Scotch whisky or tin mugs of sweet tea, Mr Smyth-Glover read the minutes of the last meeting. There was a brief discussion of membership fees and several members spoke for the record of their own recent work – Mr Salani’s dinosaurs, Miss Kitchen’s fairy dens, and so on. Then, these business matters being concluded, I was prompted to mount the dais. Looking out on a hall barely illuminated by a few oil lamps and candles I saw the upturned faces of my audience as pale, shimmering ellipses.

‘This ghost I found at a village in Devonshire,’ I began, ‘the tale whispered to me in exchange for the price of a double-handled mug of cider.’

* * *

Mr Edward Palmer was one of Mrs Duddridge’s ‘stray dogs’, as her husband called them. She met him during a talk about Africa at one of the university settlements in London.

‘I simply had to invite him,’ she said. ‘Otherwise the poor man would spend Christmas quite alone in some awful bedsitting room. He has no parents, no siblings, and no other friends as far as I can tell.’

‘He’s good company, then?’ asked Mr Duddridge.

‘Don’t be facetious, Henry. He will, I’m certain, blossom in the nurturing warmth of a family home.’

As Christmas drew near, however, Mrs Duddridge realised that there would not, in fact, be enough room at the Lodge for the numerous friends, relatives and lonely strangers she had invited. And, despite her desire to be tolerant of the foibles of others, even she had to admit that Palmer had a somewhat testing personality.

‘He has an ability to terminate conversation,’ she explained to her sister. ‘The silences are awful. What else can I do?’

When Palmer arrived at Bittlecombe on the Exeter train a few days before Christmas Mrs Duddridge greeted him on the platform and, in a cloud of polite chatter, diverted him towards the Station Hotel.

‘You will, I’m sure, be much more comfortable at the hotel and Bittlecombe is a small place. You will be able to walk to the Lodge to join us for as many meals as you like and return to your own room here when the children and the crowds and the noise become too much for you.’

Palmer, hunched and dreary, muttered something about not minding children or crowds or noise, but allowed himself to be ushered through the door of the inn.

‘You are our guest, of course, and Mr Duddridge has taken and paid for several rooms for–’ She rang the bell on the counter and tried to think of the correct turn of phrase. ‘For those among our wider circle of dear friends.’

As the hotelier carried Palmer’s single shabby bag up the stairs, with Palmer following rather too close on his heels, Mrs Duddridge called after him: ‘Dinner will be at seven o’clock if you wish to join us.’

Palmer nodded and moved his lips, indicating gratitude, but no sound emerged.

The Station Hotel was singularly gloomy and Palmer’s room, number seven on the first floor, had too many dark corners or, rather, too few lamps. Every surface Palmer touched felt wet until the slight warmth of his sallow hand chased away the fine dew. The fireplace was empty and the heavy old radiators, rusting inside and out, gave out little warmth, though making much noise in the process.

Once he had unpacked, and dressed for dinner, Palmer found himself at a loose end. He tried reading, first a newspaper, then a novel, but continually found his attention wandering. It wandered, specifically, to the door that connected his room with the next along the corridor. The door was locked and bolted. The gap at the bottom was quite dark and Palmer fancied he could feel a draught, almost a breeze, seeping through the black gap.

As if sleepwalking Palmer put down his book, rose from the threadbare armchair, and approached the connecting door. The incoming air had a faint but unusual scent, not entirely wholesome, as if something had been left out of the pantry and was beginning to turn. He placed his fingers against the thickly painted wood and fancied he felt some slight vibration. Then he pressed his ear to one of the door panels. Was there a voice? Was somebody speaking?

Palmer rarely smiled, or frowned, or allowed his face to take on any expression at all, but his brow wrinkled slightly at that faint sound. He seemed, somehow, to know the music of that voice – to recognise its faint rumble. Of whom it reminded him he could not yet say.

Anxious not to be late, Palmer set off too early, was caught in a cloudburst, and arrived at the Lodge drenched well before his expected time. Mr Duddridge was obliged to entertain him for an uncomfortably long hour. What’s more, Palmer had dressed for dinner, which the men of the Lodge rarely did, and never for these informal family meals. He sat stiff and upright with a glass of sherry pinched between his thin fingers while Duddridge lounged comfortably in a saggy brown suit.

At dinner, Palmer let the soup spoon rattle against his prominent teeth, like a gaoler’s key being fumbled in the lock, and nearly choked to death on a fish bone. Conscious of his duty as a guest, he attempted to tell an anecdote, but did so in such a low whisper that much of the detail was missed by those gathered around the table and, lacking a punchline, the tale drifted to an uncertain ending. Nobody was sad to see Palmer lurch out into the night at a little after ten o’clock.

Palmer lay between his cold, faintly moist sheets, and tried to sleep. Every time he began to drift, however, some sound or other would cause his eyes to spring open and scour the darkness of the room. The partial darkness, that is, because the drooping curtains did not quite block the moonlight, which sketched the edges of the heavy old furniture that cluttered the room. Some of the disturbing noises were easy enough to explain: footsteps on wet cobbles in the street outside; the screech of a fox; the boom of the old boiler in the basement sounding through the pipes; wood cooling and cracking. One sound, however, seemed to sit beneath these others, not exactly like a long bowed note on a double bass, but insinuating itself in that same way. It came, he was certain, from room number eight. Palmer strained to listen and even held his breath, but could not make out anything concrete. Perhaps the sound was his own blood rushing in his ears, or the beating of his own feeble heart.

There was still no light beneath the door and, indeed, the darkness there seemed deeper than anywhere else in the room. His eyes fixed on it just as his ears had fixed on the elusive sound, perceiving forms and movement which he knew were mere interpolations made by his mind in response to that pool of impossible, deep, textureless black.

He must have gone to sleep because he certainly awoke, finding the room filled with soft grey morning light, and the sound of heavy rain upon the rattling window pane. In daylight, the door looked quite ordinary and remarkable, if at all, only for its seediness.

Unable to remember if he had been invited for breakfast, lunch, or neither, he decided to present himself at the Lodge anyway. The thought of its warm fires and atmosphere of familial joy were irresistible compared to the moth-eaten gloom of the hotel.

There was, indeed, a gathering at the Lodge, and Palmer was made to feel quite welcome, eventually falling into conversation with a young man he fancied to be a nephew or cousin of Mrs Duddridge. He was a handsome fellow of about twenty five who introduced himself as Warren and, though hardly bright, shared Palmer’s interest in bicycles, their maintenance, and recent improvements in the manufacture of British machines. At lunch, Palmer avoided embarrassment by eating and drinking almost nothing. He joined a party for a walk in the afternoon and played billiards as night fell.

He was politely turned away after tea, that evening being reserved for ‘a dinner for close family’, which seemed to include everyone except Palmer. He did not notice or mind, having quite exhausted himself anxiously choosing every word and worrying about the arrangement of his long limbs for many hours on end.

He bathed and, shivering slightly, read the better part of an atrocious novel by Le Queux. By ten o’clock he was in bed and by quarter past, sleeping deeply.

What woke him some time after midnight he could not say, the only clue being that he heard himself shout into the darkness ‘No, don’t come in!’ and scrambling to cover himself. Had someone knocked? He pulled on his dressing gown and stepped into the corridor. It was empty and the only sound was the whine of wind through a cracked pane at the end of the hall.

Returning to bed, he rolled to face away from the connecting door and pulled the thin blanket high over his head. He began to recite something from Tennyson, a long verse he’d been forced to learn at school. In the pause between each line he fancied he heard an echo of his own voice, the faintest sibilance, something less than a breath.

It was now Christmas Eve and Palmer understood that he was expected to spend all day at the Lodge for carol singing, games, and other sociable activities at which he hardly excelled. He dawdled terribly, only setting out of his room at a little before eleven o’clock. He found the hotelier sweeping the lobby and cleared his throat hoping to catch the man’s attention.

‘Good morning, sir.’

‘Um,’ said Palmer.

‘Yes, sir?’

‘Is there…’ He coughed. ‘Is there a guest in room eight? The room next to mine?’

The hotelier blinked and shook his head.

‘It’s only you at the moment, sir. Another guest of Mrs D is due today, I believe, but I’d thought I’d put him in number ten.’

Palmer rotated his hat in his hands.

‘Not number eight, then?’

The hotelier looked peeved for an instant then corrected himself.

‘Well, sir, no, because truth be told, that room is in need of some repair. Pigeons got in last winter and made a rotten mess.’

‘Ah, yes, pigeons. Noisy creatures.’

He was able to ascribe all the disturbances of the preceding nights to this colony of pigeons, even though he’d heard nothing resembling cooing or the flapping of wings. It was enough to know that there might, indeed, be a living presence of any kind in room eight.

The improvement in his mood carried over to the Lodge where over lunch he managed to successfully respond to questions from a young lady called Miss Day with questions of his own, maintaining quite a successful rally. He told a joke he’d heard in the office which, for once, was both funny and inoffensive. Someone slapped his back and called him a ‘good fellow’ which he found to be an entirely novel experience.

Mr Warren sought him out after lunch and invited him to inspect his bicycle, a brand new Rudge-Whitworth.

‘You must try her out,’ said Warren. ‘Pneumatic tyres are the only thing for the countryside.’

Palmer accepted this invitation and cycled up the drive, out into the lane, and around the village square, returning with ruddy cheeks and an appetite some twenty minutes later.

Mrs Duddridge observed Warren and Palmer with an indulgent smile, as if to introduce them had been her plan all along.

As evening came, sherry and port were consumed, and Mr Palmer also drank two bottles of double stout supplied by one of the servants. This gave his carol singing a certain confidence if not contributing to its precision.

Towards midnight, Mr Warren gave Mr Palmer a piggyback ride, and Mr Palmer returned the favour. Mrs Duddridge was not quite sure whether to be amused by these boyish escapades. Eventually, catching Mr Warren’s eye, she pursed her lips and gave a small shake of her magnificent head.

Mr Duddridge decided that a late supper was required and went to the kitchen himself, returning with a loaf of bread, a wedge of cheese, and something on a stand covered with a fine lace doily. He placed these items on the table and, with a proud flourish, whipped away the covering to reveal a quivering cake of brawn. The aspic had been tinted pink and slivers and chunks of meat were suspended in it like jewels.

‘What do you think of that?’ said Mr Duddridge, prodding the brawn with a finger.

Mr Palmer blanched, staggered, and was promptly sick behind the piano.

The party broke up and Palmer found himself once again ejected into the darkened lane, with a foul taste in his mouth and the beginning of a sore head.

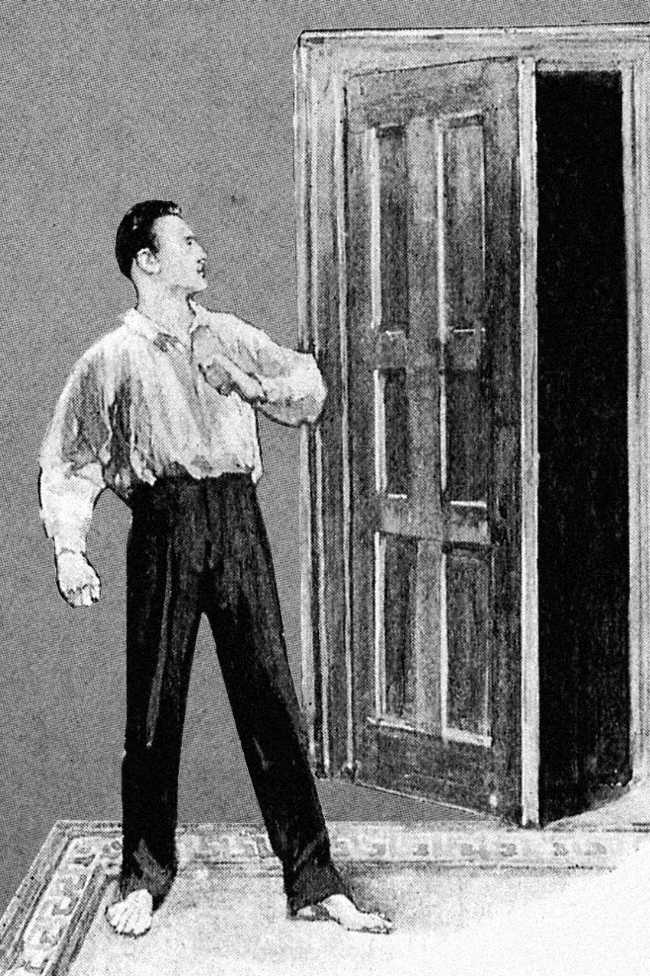

He was in his room just as the church bells began to ring midnight, announcing Christmas Day. The rusting radiator had been on all evening and was practically steaming with heat. Feeling nauseous and overdressed, Palmer disrobed in a disorderly, rather frantic fashion, casting his waistcoat one way and his threadbare silk scarf another. It was only when he’d stripped down to his wooly combinations that he noticed, first, a cold draught and, secondly, a sharp line of moonlight.

The connecting door was open. It seemed to be inviting him in. The stench of rotten meat both repelled and enticed him.

He stepped closer, his bare feet turned inward.

‘I say,’ he whispered, unable to stimulate his vocal cords into meaningful movement. He coughed and tried again. ‘I say, is there somebody there?’

There was no answer but the silence had weight, like those occasions when his mother had refused to speak to him for days on end.

He pressed his flat fingertips against the door and pushed it, gently, until he could see into room eight.

The room was dark, except for the moonlight through the filthy windows, but that was enough to etch in silver the form of a person lying upon the unmade bed. No, several people. No, two people locked together. No, one very large person with many limbs. No, the carcass of an animal, or a mass of whale blubber, studded with wet, swivelling eyes, and weeping pearlescent liquid.

He lurched away and slammed the door shut, but it did not catch. As it bounced away from the frame, opening itself wide for a second time, it revealed a young man, naked, sitting on the edge of the bed. He pressed a hand to his own bare chest and then held it out to Palmer. Moonlight caught the dark, wet surface of the palm.

‘Waterloo,’ said Palmer.

The young man in room eight did not reply.

* * *

Glancing across the faces of my audience in the old chapel, I shrugged.

‘The story as it was told to me was pieced together from gossip in the village. Palmer’s own account was the primary source, delivered to the police and circulated through friends and relatives of the village constable. They found him in room eight, undressed and cold, having written the better part of his confession on seven sheets of hotel notepaper.’

Miss Kitchen’s hand went up.

‘Confession?’

‘That business in the Cut last summer. The clerk, the sailor, the public house barman. Palmer admitted to all three.’

‘Was there no trial?’

‘Palmer died in his cell at Exeter. Mr Duddridge kept the story out of the newspapers not wanting the Lodge and its Christmas parties to be tainted by association. How he died, in a locked cell, with knife wounds to the chest but without the slightest sign of a weapon, is a puzzle in its own right. One for Doctor Dutoit and his study of black magic, perhaps.’

Dutoit nodded from the back of the hall.

‘It has to do with doors,’ he said, his low voice echoing from the bare boards and plain white walls. ‘They cannot be relied upon. They are unstable.’

With that perplexing thought, the meeting concluded, and we took our leave of each other, wandering out into what had become a settled fog, heavy with the scent of woodsmoke.

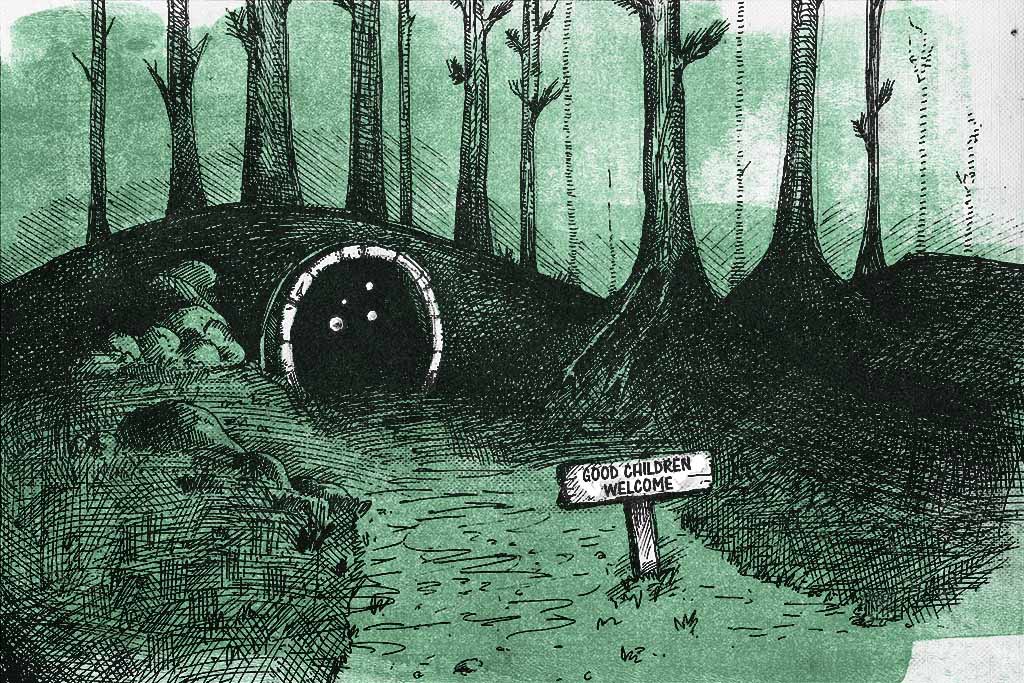

Main image: my own photo overlaid with a design borrowed from an Edwardian book, and text in a font scanned from an old type specimen manual, manipulated with textures from texturelabs.org. In-story illustration adapted by me from one created by Sidney Paget for the Sherlock Holmes story ‘The Adventure of the Beryl Coronet’. I did not use any artificial intelligence tools to create these images, or any of the text.