It’s been interesting to see conversation in the past week about working class access to culture prompted by Jeremy Corbyn’s appearance at Glastonbury.

Personally, though I get where they’re coming from, I’d like commentators to think twice before implying that to be working class is to be essentially lumpen, leaden, tasteless and disengaged.

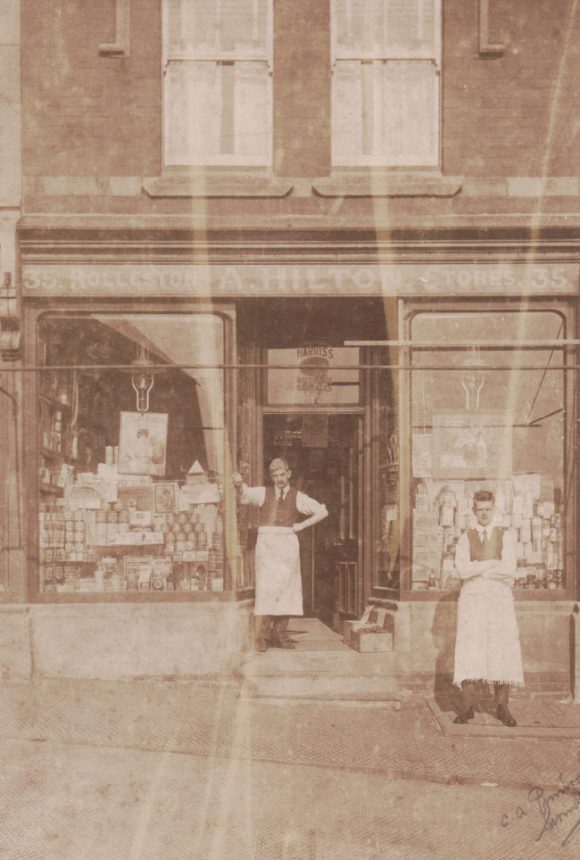

I grew up in a working class family, mostly on a council estate in Somerset, and mostly skint, but there was culture everywhere, assuming you don’t define culture only as Shakespeare and Beethoven.

There were libraries, both in town and at school, where idealistic librarians delighted in the slightest sign of enthusiasm on the part of kids like me. They went out of their way to push cool books and to acquire books by authors in whom I showed any particular interest. By the age of 16 I’d read, for example, Joseph Conrad, James Ellroy, William Gibson, Ernest Hemingway and Philip K. Dick. (All a bit male, I realise, but I’m working on that now.)

I had teachers who refused to talk down, either in terms of age or social class, and lent or gave me copies of books by C.S. Lewis, Raymond Chandler, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Mikhail Sholokhov. (Actually, I never got round to reading that last one…)

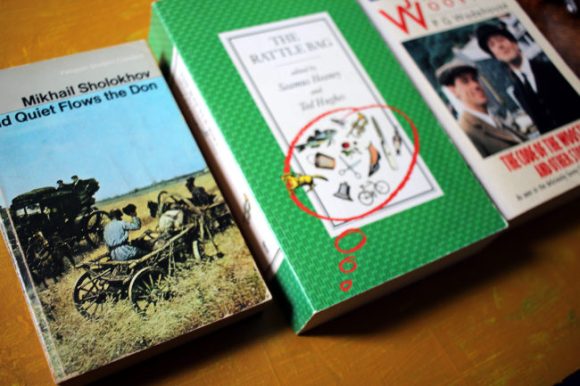

And, though I didn’t realise it at the time, the bearded socialist in the Lenin cap who ran the secondhand book stall in my home town was carrying out practical redistribution when he tipped me off to an unadvertised five-Penguin-paperbacks for a pound offer. I built a library that way, stacking my rickety shelves with everything from George Orwell to P.G. Wodehouse, via Len Deighton and Dashiell Hammett. Libraries are great but owning a book — scribbling in the margins, bending the corners, dipping in and out over the course of years — is different.

Then there was Auntie, and her extended family. When I started to develop a serious interest in films as a young teenager I didn’t need an art-house cinema because I had the BBC and its lingering Reithian desire to improve and educate. There was Moviedrome, for example, which saw Alex Cox beaming the cultest of cult films into the corner of my bedroom. (I inherited my Nan’s nicotine-stained punch-button TV and VHS recorder when she upgraded. Something something flat screen TVs something something benefits.) And I remember being floored by a season of film noir in about 1993 where I saw things likeThe Big Combo and Double Indemnity for the first time, book-ended with serious-minded discussion and accompanying documentaries. Meanwhile, Channel 4 gave us the Banned season which my friends and I stayed up to watch hoping for titillation but came away from having seen The Life of Brian, fully contextualised as part of a serious debate about censorship. I started listening to Radio 4 at about the same time — hours a week of quality drama (Clive Merrison is the best Sherlock Holmes) and discussion of varying degrees of intellectual rigour running as background noise, drip-feeding my brain.

My parents not only encouraged my consumption of culture but also set a good example. My Dad has been a serious, obsessive fan of blues music since he was a teenager on his own Somerset council estate. Though he’s not a great reader in general he will read about music and so our house was always full of heavyweight volumes by American musicologists, either borrowed from the library or (the secret weapon in many working class bookcases) cancelled and sold off by the library service for 10 or 20p. He also introduced me to Alfred Hitchcock, spaghetti westerns and Hammer horror; to the Kinks, the Bluesbreakers, and the Pretty Things. All, with hindsight, pretty hipster cool for a small-town lathe-operator.

Mum is and always has been a reader — one or two books on the go at any time, speeding through the pages, always keen to explain why she likes or dislikes any particular book. She expected me to read and to enjoy reading and — not in a pushy parent way, but quite naturally — and it worked; I did, and I do. On a couple of occasions she even tried to write novels — Mills & Boon romances, I think — on a typewriter in the dining room. She didn’t get far but that sent a powerful message, too: just because we’ve got fuck-all, and live somewhere like this, doesn’t mean we have to be passive — we’re allowed to create! I started writing myself on the typewriter she abandoned. (Or did I just steal it from her?) I suppose Dad’s various bands over the years, and his dabbling in songwriting, underlined that point.

When I went to university I was sure I would be at a disadvantage and, sure, I sometimes felt a bit lost when people started to compare experience of going to the theatre — to date, I’ve seen, I think, four plays, ever — that is a world from which I feel cut off. In many ways, though, I felt more rounded in my education than some of my peers, and more confident in my own sense of what was good and bad, and what was worth studying in the first place.

I worry sometimes that the infrastructure I enjoyed has been eroded. Libraries have closed or become less ambitious, and TV seems less willing to lecture or challenge in case it gets accused of being patronising or pretentious. But then I hear a story about a refugee in the Lebanon learning to play the violin largely from YouTube videos, and remember the existence of, say, Project Gutenberg, or Archive.org, and I think, no, there’s reason to be optimistic. There’s more culture to enjoy, and more cheap or free ways to enjoy it, than ever before.

And if there’s one thing we council types are good at it’s stretching scraps and mince out to a full meal.