Some People is a little-known social realist film from 1962 that offers a glimpse of a post-war Britain rarely seen on screen. It is not set among northern terraces or the slums of the East End of London but on the docksides and gleaming new council estates of Bristol, the capital of the West Country.

When I moved to Bristol last year I wanted to get to know its culture and so asked around for tips on which novels and films best represent the city. Some People was one of the suggestions and after a little hunting I found a DVD released by Network in 2013.

It was lying on the coffee table when my then 69-year-old Dad visited and he recoiled at the sight.

“Is that… Is that Some People?”

“Yes. Why?”

“Oh, nothing,” he replied, still eyeing it with suspicion, and I knew there was a story to tell.

His reaction prompted me to watch the film sooner rather than later.

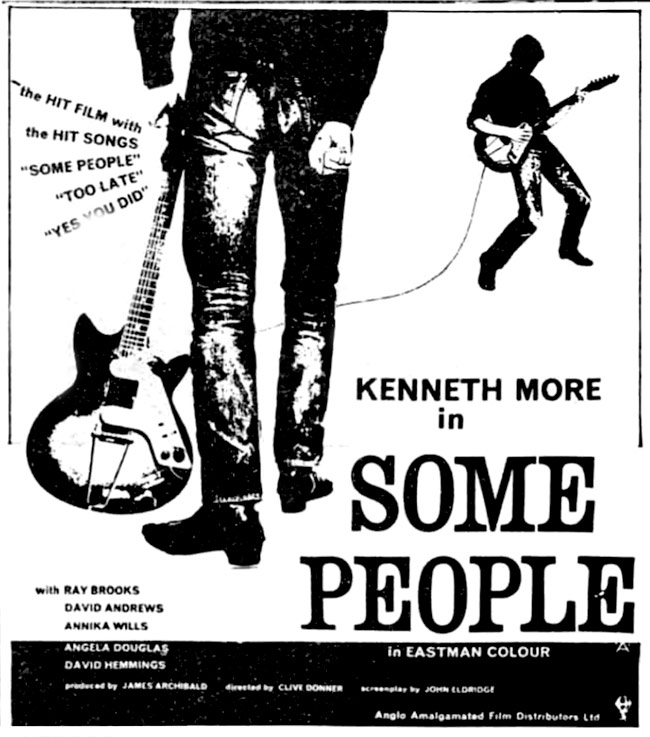

It was directed by Clive Donner who would make a name for himself with The Caretaker in 1963 and then head to Hollywood to make What’s New Pussycat? In 1965.

While Some People is clearly the work of a director finding his feet it is nonetheless an enjoyable drama about a teenager, Johnnie, played with charm and intensity by Ray Brooks, and his struggle to choose between straightening up or continuing a descent into delinquency.

Johnnie and his friends Bill (David Andrews) and Bert – a baby-faced David Hemmings – get into trouble racing their motorbikes along the Portway on the banks of the Avon and are banned from riding them which leaves them frustrated and deepens their boredom.

Then one night, while messing around in a church they’ve all but broken into, they are taken under the wing of Mr Smith, a local youth group organiser played by veteran British actor Kenneth More, who encourages them to form a pop group.

Bill rejects Mr Smith’s mentorship seeing in it an attempt to control him and breaks with Johnnie and Bert, falling in with a gang of hard-cases.

Then, fuelled by jealousy over his girlfriend’s attraction to Johnnie, Bill tries to sabotage his friend’s new found stability. It’s small stuff – squabbling and scrapping, hardly Marlon Brando territory – but that makes it feel all the more authentically British.

The film’s strengths are its cast, setting and its considerable charge of nostalgia.

Filmed entirely on location, it captures the reality of Bristol in the heat of post-Blitz reconstruction, half tumbledown harbour city, half planners’ dream.

A large part of the action takes place on the Lockleaze estate, high on windswept Purdown in the city’s northern suburbs.

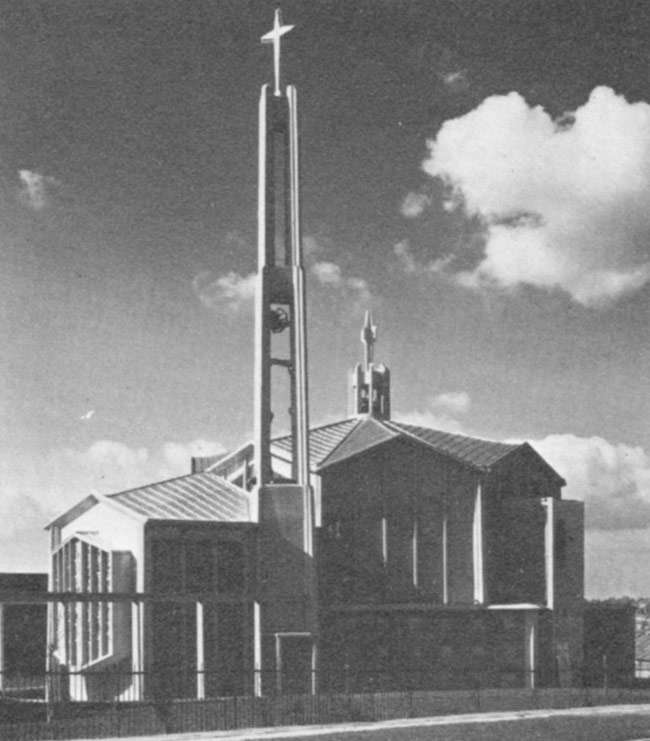

St Mary Magdalene with St Francis church is one of the stars of the production – a mad modernist vision in concrete and stained glass that provides a surreal sci-fi backdrop to the boys’ antics. The church opened in 1956 and was typical of the space age houses of worship built on overspill estates all over the country in the post-war period.

Unfortunately, though it looked astonishing, it was plagued with structural problems and was demolished in 1994, which only adds to the value Some People holds as a record of a time and place.

Another particularly striking scene takes place in the Palace Hotel, an especially grand Victorian pub on Old Market. There Johnnie has a breakthrough conversation with his taciturn working class father played by Harry H. Corbett (whose Bristol accent, it must be said, ends up drifting to somewhere near Cork). Real pubs are rarely seen on film, especially in colour, and this is a particular lovely example – cast iron tables, a beaten up piano, everything dark with age, the aroma of smoke and stale beer positively wafting from the screen.

Those with an interest in public transport will thrill at the plentiful footage of the famous Bristol ‘Lodekka’ buses while aviation geeks will get a similar thrill from scenes of Mr Smith at work: when he isn’t encouraging young tearaways to play nicely together he is an engineer overseeing test flights of the Bristol 188 ‘Flaming Pencil’ supersonic jet.

Anneke Wills plays Mr Smith’s daughter, Anne, who has a teenage fling with Johnnie. His influence leads her to buy tight jeans which she further shrinks to fit in the bath. You’d think this scene a little ripe if it turned up in a modern period drama set in the 1960s but here it is charmingly authentic.

In general the film is a useful reminder that in 1962 kids were still wearing quiffs and leather jackets.

Passing scenes of dancehalls, espresso bars and roadside motorbike hangouts will also bring back memories for anyone who was on the scene in the 1960s. Less thrilling but no less evocative are the bus stations, council houses and cigarette factories where real life plays out between bouts of fun or violence. It isn’t Grim Out West, only a little grey, a little sparse, slow and sleepy.

If Some People has weaknesses they are the score – square rock’n’roll arranged by Ron Grainer and performed by local Shadows wannabes The Eagles – and the fact that it is effectively propaganda for the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Scheme which part-funded the production. I say ‘effectively’ because Bill, the rebel, delivers several stinging diatribes against it and, frankly, seems much cooler than Johnnie and his gang of goody-goodies.

Once I’d finally watched the film I was more curious than ever about Dad’s reaction and pressed him on it when we next went for a pint. With some reluctance he told me the story.

Like Johnnie, Bill and Bert, he and his 14-year-old friends on a Somerset council estate were often bored and got up to mischief. When it wasn’t joyriding, it was repeatedly breaking into the local CO-OP to steal cigarettes.

One night he returned home to find his father in a foul temper.

“Where have you been, boy?”

“In town to see Some People.”

“Oh, yeah? Some People? Well while you’ve been out, some bloody people have been here to see you.”

The people in this case were the police and Dad ended up with a criminal record.

After that, like Johnnie in the film, he started a rock group and threw his energy into making music rather than trouble, before settling down to a life working in factories and warehouses.

Art imitating life imitating art.