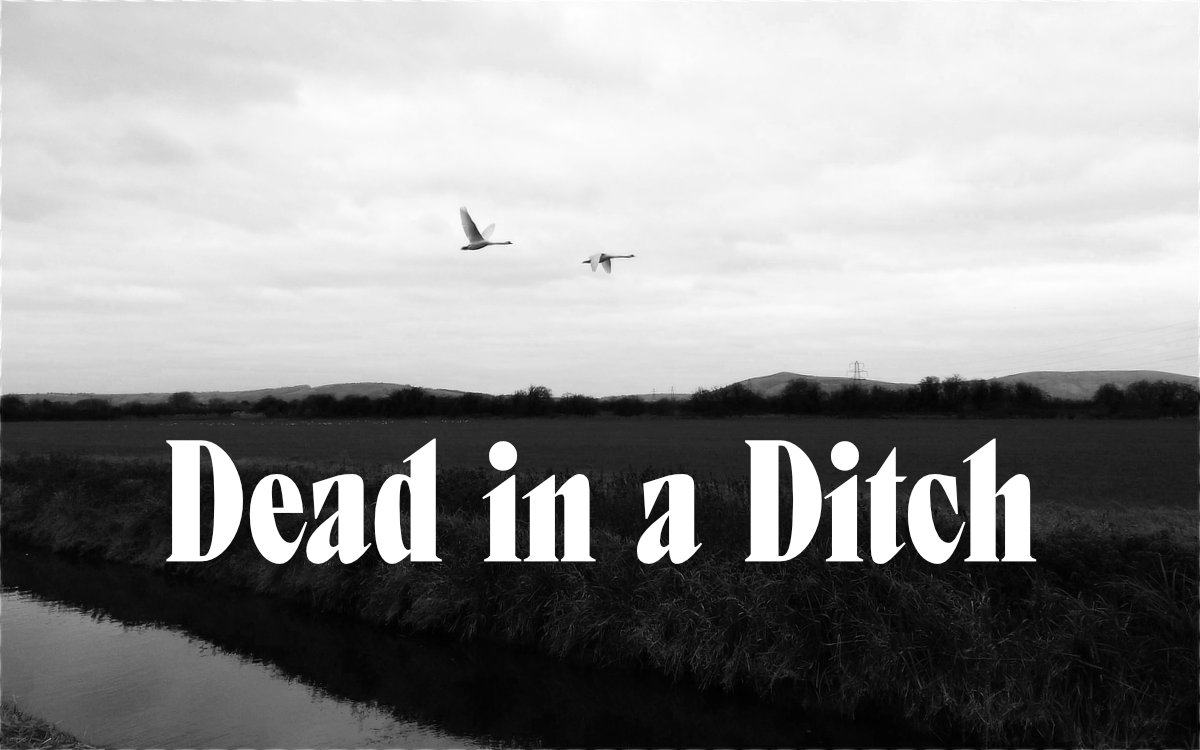

Where is the worst place you could end up haunting? I reckon my spot’s a contender. It was bad from day one, standing knee deep in the green water of a ditch, looking down on my own smashed body in the half-submerged hatchback.

Then it took them three months to find me, even right there by the main road between town and the village, because the reeds were high. I watched my body bloat and fart bog gas and liquify. I watched rats and insects help themselves to my flesh. I saw my bones emerge like the wreckage of a ship on the shoreline with the tide sliding out.

I tried not to look. I took an interest in the clouds in the big sky above the levels, and in the trees as they began to yellow at the edges and drop their leaves. I watched sunrises, sunsets, and stared at the stars – I could see them so clearly out there in total darkness. I counted cars, too, as they flew by. You’re going too fast, I thought, and remembered that people kept saying that to me, too.

Then, when the trees were bare with black branches, a car passed slowly enough that a child in the back seat saw the low sun catch the roof of the wreck. The car stopped at a layby a little way along the road into town. I could hear the burr of its engine and the tick of its hazard lights above the breath of the westerly wind. The police car came a little later and the road was closed. Then an ambulance. Then, just after dark, a forensics team with floodlights and tents. Finally, a pickup truck from a garage in town arrived and, by dawn, the car was gone, and it was just me and the dirty water around my jeans.

Mum and Dad came, parking at the roadside. Cars kept passing at twenty above the limit, one or two honking their horns in irritation at the blockage in the road. My parents couldn’t see or hear me as I murmured to them: ‘It’s alright, don’t miss me, don’t feel pain for me…’ Before they departed they left a stuffed monkey, a bunch of flowers in a heavy stone pot, and a card I couldn’t read. In the weeks that followed I watched the card blow away in the wash from an articulated lorry, the monkey turn ragged and grow green mould, and the flowers rot to black stalks. I didn’t see Mum and Dad again. I suppose they drove the long way round to town after that, so as not to have to think about me.

After a long while I got tuned into the other dead around and about. There was a pale smudge in the field opposite that I thought must once have been a woman. She seemed young and was always stooped, always weeping. The sound sometimes carried on the wind. She might have been there since the Civil War, or long before. One night in June I watched a Douglas C-47 with black and white invasion stripes on its tail pass silently overhead and fade out of existence somewhere over the old airfield. I learned that the famous Headless Horseman was real, too, though less glamorous than in the stories they told around town. He passed by, once a month or so, and was a nasty old thing. He had a dirty tunic streaked with brown blood and his head was in his lap, crushed and misshapen, but still screaming. He was always in a hurry to be somewhere. On summer evenings, if there wasn’t too much traffic, and the wind was right, I could hear the sounds of the battle of 1685 being replayed on the field outside the village. The teachers from the village school used to take us there to camp out, and tell us ghost stories as we toasted bread over a fire.

Years must have passed before I saw Dani again. I’d dropped her off in town before making that last journey and I suppose she had no reason to come to the village after I’d gone. Then one day, there she was, in the driver’s seat of her own hatchback, framed in the open window. She was a little older but no less beautiful. After the car had passed I realised there was also someone in the passenger seat. An hour later, she drove back and I saw her for another two seconds, a face in shadow, her hands on the wheel. I also saw that the man sitting next to her had a broad chest and tidy beard.

I’d always wondered how eternity would work. Wouldn’t you get bored? In life, I could hardly sit still, and was always after a distraction or a thrill. That’s probably why I drove so fast all the time, to feel not-boredom for a few minutes. But boredom, it turns out, is only a problem for the living. It comes out of being anxious the whole time about your status and how much you’ve achieved. It does us all right in the survival game. It keeps us moving and exploring. In death, though, you let time wash over you in an endless stream. I wasn’t waiting. I didn’t expect anything, or hope for anything. I just was, and just am.

If there was anything I longed for, and longing’s too strong a word, it was to see Dani again. When I died, the wires that connected me to the world were cut, but the cut wasn’t clean. An intermittent contact made me feel something, or remember how it felt to feel something, or something like that.

She passed along the road many times after that. Alone in the car; with the man; following a removal van; dressed for work in her supermarket uniform; dressed for a Christmas party in a sparkling silver dress, with the man in a shimmering suit; and in a wedding dress in a vintage car with ribbons tied to its radiator. Their car got bigger, the backseat gained a baby seat, then a baby, then two babies. They drove too fast, of course, because everyone did. The car hugged the bend, lifted a little one one side, always ready to tip.

Through cycles of sun and moon, summer and winter, flood and drought, I stood there with water boatmen skidding around my knees, and rats circling. The creatures knew I was there, somehow, in some simple way, because they never touched me, or went through me, or whatever would have happened.

There was no way for me to make any difference in the world, I knew that for sure. Still, I always wanted Dani’s car to break down as it passed me, so I thought hard about it, and one day, it did. I felt as if I’d made it happen. The engine cut out and she began to drift. She guided it into the verge and put on the hazard lights. Then she got out and walked along the road directly in front of me.

Her fine blonde hair had just begun to turn grey and there were new folds and grooves around her eyes. Speaking into her phone she said:

‘About halfway, yes, just past Crockford Farm.’

It was the first time I’d heard her voice in all these years and I experienced something like a memory of how it felt to yearn for someone. I remembered, for a sliver of a moment, how a sweet harvest apple tasted and what it meant to smell the sea.

While she waited for the mechanics to come, she leaned on a gate and, resting her chin on her arms, looked out over a field of yellow rapeseed.

Did she remember this was where it had happened? Did she ever know?

The recovery vehicle came, its orange lights throwing twists of fire on the surface of the filthy ditchwater. Within a few minutes the engine of her car was turning over. She put the radio on and I heard two bars of a song I didn’t know before she waved to the mechanic and sped off.

Over the years, Dani kept passing, back and forth, like an irregular pendulum, village to town, town to village. The car changed, and she changed, but I didn’t.

Her children got their own cars, which they drove much too fast, and I wondered if she ever used my story as a warning.

One day, after I suppose decades must have gone by, Dani appeared dressed in black in the back of a limousine, following a hearse.

A few years after that, the hearse passed again, and this time Dani’s children were in the black car that followed.

That night, the Headless Horseman passed, screaming mad, as usual. I screamed back.

If you enjoyed this story you’ll probably also enjoy my collections Intervals of Darkness (2024) and Municipal Gothic (2022).