Why is my novel called The Grave Digger’s Boy? Well, finding out is part of the fun, but here’s something I’ve kept a bit quiet until now: I’m a grave digger’s boy.

For a year or so when I was at junior school, my dad had a job as a grave digger for the council.

At the time, I thought this was pretty cool. I enjoyed telling other kids who would either recoil or want to know more.

There certainly were macabre stories – days spent opening up old graves so the newly-dead could join their spouses or siblings, boots through the rotten lids of coffins, slips and falls among the mud and bones…

But it was also utterly mundane. Rotas and requisition orders, job sheets and sheds. Cheese and pickle sandwiches in the back of the van, sheltering from the rain.

Part of being a writer is throwing different ideas into your brain and letting them bounce around until they stick together in interesting ways.

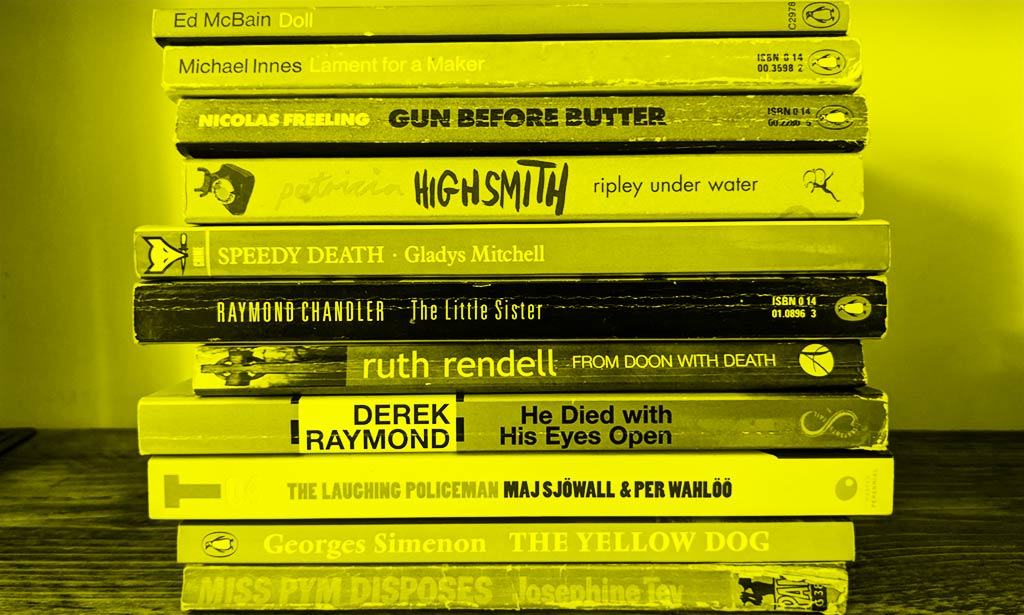

So if The Grave Digger’s Boy is ingredient one, here’s number two, freshly added: John Braine’s The Vodi, which I came across as part of my #reading1959 project, has been described as ‘kitchen sink gothic’ – bleak social realism with an added flavour of the sinister supernatural.

Suddenly, I realise that lots of things I’ve written or have been working on that I’d thought were separate and distinct, aren’t.

For example, there’s my big work in progress – the epic novel I expect to finish in a decade or so that I jokingly refer to as War and Peace but set on a council estate. When I launched into writing last year, something happened that I hadn’t planned or expected: incidents of the uncanny began to manifest in what was supposed to be raw realism.

Here’s an example, from the opening, set in 1957, as two central characters arrive at a half-built council estate after dark, late at night:

John Patrick slammed the brakes on and the little car jerked to a dead stop. He turned off the headlights and they sat in the dark as the engine ticked.

‘Will you bloody give over? We’re nearly there.’

Another sigh, softer, came from between her dark lips.

‘You’re gorgeous, you are,’ he said after a moment. ‘Like a film star.’

She tutted. ‘Well? Go on, you daft sod.’

He looked at her for a moment longer and then pushed a lick of his brown Bryclreemed hair back into place behind a big ear.

‘It’ll all look better in daylight.’

He switched the lights back on and they both started.

Staring back at them from the road was a big cat, as big as a man, with oily black fur and eyes reflecting back as yellow stars.

Irene shrank back in her seat.

The engine purred.

The cat licked its lips, yawned, and bolted away.

After a few seconds, Irene cut into the silence.

‘What the bloody hell was that?’

With a shaking hand, John took the cigarette from between his lips, snuffed it, and tucked it behind his ear.

‘A large female yaws,’ he said.

‘Yaws? What’s a yaws?’

‘A-Mild and a-bitter with a whisky chaser, a-thank you kindly.’

Elsewhere in the story, there’s the ghost of a dead sibling and an echo of Bella in the Wych Elm – “Who Took Mary Cook?” The UFO my dad swears blind he saw might turn up, too.

Another novel, abandoned for now, tentatively titled The Red Lodge, combines the case of the Lamb Inn haunting with the modern trend for buildings ‘protected by occupation’:

“Charlie boy!”

A hand on my arm, those fat digits digging into my bones.

“I’ve missed seeing you.”

“Hello, Uncle Bernard.”

His hand dropped away and he looked me up and down.

“You look like shit,” he said, rummaging in his pocket for a bunch of keys.

I said nothing.

He slapped flatfootedly towards the temporary steel gate with its warning signs and chains and opened the padlocks one by one.

Together, we dragged the gate across rough concrete, scratching a white semi-circle.

Bernard drew on his vape stick and exhaled a blueberry flavoured cloud around his unruly head as he considered the overgrown driveway.

“Got decent boots on? Let’s walk.”

I looked down at my well-worn, thin-soled Adidas trainers, but didn’t protest.

“It’s a lot of land,” I said, partly to break the uncomfortable rhythm of our synchronised steps.

Amid the brambles were the remains of concrete and brick structures, pieces of pipe cut off a few inches above ground, and chunks of rusting machinery. Here and there were burst bags of rubbish, hurled over the fence and left for rats and gulls to tear apart. A lone shoe grew moss.

“Lovely, isn’t it?”

He wasn’t being sarcastic – to Bernard, it really did look beautiful, a virgin plain beyond the frontier.

“They built parts for planes here before the War, until they moved production under Salisbury Plain.”

The house was getting nearer, flooding the horizon with a wall of red.

“There were Italian prisoners of war here until 1947, working on the farms.”

Beneath our feet, concrete gave way to smooth asphalt and Bernard began fingering his keys again.

We stopped at the doorway with its clamshell hood and four white stone steps as Bernard muttered to himself, irritated: “Fucking thing… Checked it before I left the office… Should have… Fuck sake…”

I could hear the motorway in the distance – a constant exhalation – and the wind shaking the brambles, but there was also something else – a high, secret sound.

A signal.

And, of course, right in plain view, I’ve been writing about haunted council houses and factories:

In more concrete terms (no pun intended) is there perhaps something about the way the houses were constructed? In the Sunderland case journalist Ken Culley slept in the haunted bedroom but, despite apparently making every effort to spook himself, saw no evidence of anything supernatural. What he did observe was that the construction of the house made it simultaneously cold and stuffy, and that opening the window caused a localised breeze to swirl around the foot of the bed, numbing his feet. Light and airy may have been the intention but large rooms with high ceilings, sparsely furnished, offer great potential for echoes, reflections and strange circulations.

Focusing on the connections between all of this, more items from the memory banks presented themselves – a body of family stories, from the morbid Lancastrian side, that must have settled in my subconscious.

Greaty Aunt Ann, for example, who tried to kill herself by walking into the sea but came back to shore to get an umbrella when it started raining.

The great-great-uncle who tramped around the country during the depression of the 1930s sleeping in graveyards: “They’re safer than anywhere else; it’s the wick ‘uns outside you’ve to worry about.”

A vague tale of a relative, or family friend – urban legend, more likely – who worked as night-watchman at a funeral parlour and ran screaming from the premises when at two in the morning, through the action of tightening muscles and trapped air, a corpse sat up and groaned at him.

My grandmother’s story of a childhood acquaintance from Crawshawbooth who awoke to find a rat that had eaten its way into her bedroom from the attic chewing at the tip of her nose and cheeks.

My current project, which I’m unsubtly trailing on Twitter, sits in the same territory – the darkness of recent past, the modern world weighed down by the old, blood on the lino.

‘Kitchen-sink gothic’ is good – and there’s an anthology that uses that title. I gather ‘gothic realism’ is also a term that sometimes pops up. But I prefer ‘municipal gothic’, perhaps because it suggests a Venn diagram of two of my favourite projects, Hookland and Municipal Dreams.

I’ve been writing municipal gothic by accident until now but I reckon it’ll be deliberate from here on.