Everything about the American serial killer Charles Schmid sounds pathetic – so how was he able to command the loyalty of his teenage followers?

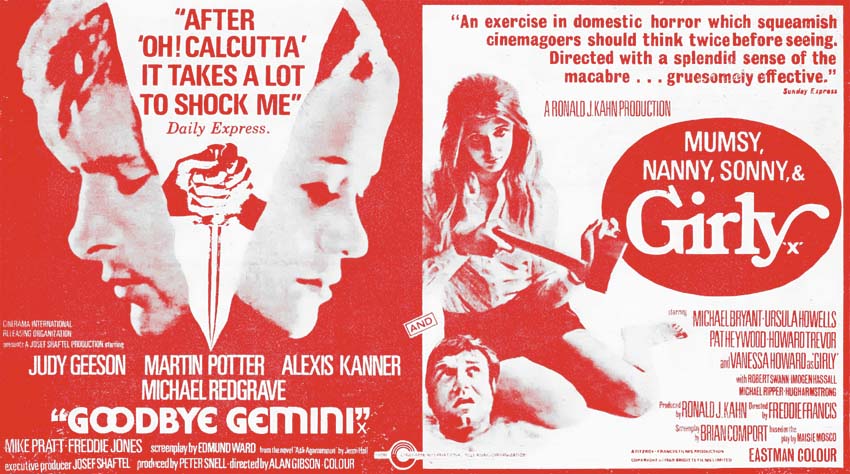

That’s a question grappled with by two films based on Schmid’s story, 1971’s The Todd Killings, directed by Barry Shear, and 1985’s Smooth Talk, directed by Joyce Chopra.

Both films ultimately share the same original source: a 1966 Life magazine article by Don Moser called ‘The Pied Piper of Tucson’.

That article is a masterpiece of true crime writing, available online, and also collected in a 2008 Library of America anthology. Moser painted a picture of a loser and weirdo who, in his early 20s, was still hanging around with school kids in Tucson, Arizona:

At the time of his arrest last November, Charles Schmid was 23 years old. He wore face make-up and dyed his hair. He habitually stuffed three or four inches of old rags and tin cans into the bottoms of his high-topped boots to make himself taller than his five-foot-three and stumbled about so awkwardly while walking that some people thought he had wooden feet. He pursed his lips and let his eyelids droop in order to emulate his idol, Elvis Presley. He bragged to girls that he knew 100 ways to make love, that he ran dope, that he was a Hell’s Angel.

But Schmid was somehow appealing to teenagers who saw not a creep but a local own-brand version of Elvis Presley:

He had a nice car. He had plenty of money from his parents, who ran a nursing home, and he was always glad to spend it on anyone who’d listen to him. He had a pad of his own where he threw parties and he had impeccable manners… He knew where the action was, and if he wore make-up—well, at least he was different… [To] the youngsters – to the bored and the lonely, to the dropout and the delinquent, to the young girls with beehive hairdos and tight pants they didn’t quite fill out, and to the boys with acne and no jobs – to these people, Smitty was a kind of folk hero. Nutty maybe, but at least more dramatic, more theatrical, more interesting than anyone else in their lives: a semi-ludicrous, sexy-eyed pied piper who, stumbling along in his rag-stuffed boots, led them up and down Speedway.

Schmid was more than “nutty”. He tortured at least one cat, for starters. Then, in May 1964 he convinced two young friends to accompany him as he kidnapped, raped and murdered 16-year-old Aileen Rowe. They helped him bury the body in the desert – and kept his secret.

A little later, in the summer of 1964, he met 16-year-old Gretchen Fritz at a swimming pool. He seduced her and they had a rocky year-long relationship. It culminated in the death of both Gretchen and her younger sister, Wendy, in August 1965. When he showed a friend called Richard Bruns where the bodies were buried in the desert, Bruns turned Schmid into the law.

Schmid was convicted of murder in August 1966 and sentenced to death. By June 1967 a film based on the story was in production.

The Todd Killings: torn from today’s headlines!

The Todd Killings had a range of working titles like ‘Pied Piper of Tucson’, ‘The Pied Piper’ and ‘What Are We Going to Do Without Skipper?’

It was eventually released in 1971 with the action relocated from Tucson to the fictional town of Darlington, California.

Schmid became ‘Skipper Todd’ played by Robert F. Lyons, with his look and lingo brought up to date. Skipper has shaggy Mick Jagger hair, tight bell bottoms, and a green dune buggy. He also plays folk rock songs on an acoustic guitar, almost like a spare member of The Monkees, or Charles Manson.

Lyons really is good looking, though, and brings to the part a commanding arrogance. The children follow him because he has the qualities of a leader. In odd, intercut scenes he is shown lying to a US Army recruiter to wriggle out of fighting in Vietnam where, actually, he might have thrived as another William Calley.

Updates and poetic licence aside, the film is an otherwise relatively faithful recounting of the facts of the case.

It has a particularly strong opening: Skipper is burying a body in the desert, helped by a devoted young girlfriend and a panicky boy.

This is not a whodunnit, or a did-he-do-it, like Psycho. That this young man is bad is established from shot number one.

From the off, we also empathise with the bored kids who are groomed by Skipper Todd, even as we want to shake them by the shoulders and urge them to break free.

We even begin to understand why they would reward his madness and violence with devotion. They are weak, and their parents are weak, too. He is good at spotting weakness and filling the gaps in people’s live. He has everyone, both boys and girls, under an erotic spell.

Did Charles Schmid ever see The Todd Killings? He died in prison in 1975 so it’s just about possible. If so, he would probably have found it flattering.

Smooth Talk: back to the future

More than a decade later a second film tackled the story more obliquely, and more artfully. Joyce Chopra’s Smooth Talk from 1985 was not based on Moser’s article but on a short story by Joyce Carol Oates, ‘Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?’ first published in 1966.

In Oates’s version of the Schmid affair, which was distilled from Moser, the monstrous fake teenager is called Arnold Friend. He stalks, seduces and seizes a teenager called Connie while her well-to-do parents are out at a barbecue. It crams a lot into a few thousand words and presents small town America as a menacing, sickly place.

Smooth Talk expands on the short story significantly, using Oates’s original material to form only the final act of the film.

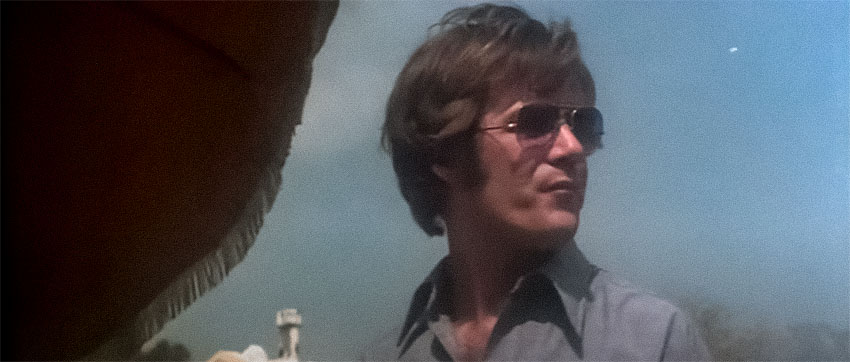

It also does something really clever with the period. Connie (Laura Dern) is a quintessential 1980s teenager straight out of a John Hughes movie, while Arnold Friend (Treat Williams) is a relic of the 1950s. He is a cheap knockoff of James Dean (Connie has posters of Dean on her bedroom wall) and therefore closer to the real Charles Schmid than Skipper Todd.

In this, there’s an echo of another film: Terence Malick’s Badlands from 1973, in which Martin Sheen based his performance as spree-killer Kit Carruthers on James Dean. Kit wasn’t based on Charles Schmid, however, but his near namesake, Charles Starkweather – another rural weirdo with a taste for teenage girls.

In some ways, Arnold Friend is a less complex character than Skipper Todd, or the real Charles Schmid. He’s a sinister stranger, not a ‘pied piper’ who everyone knows and admires. He’s clearly a much older man (Williams was 34 when he played the part), dressed anachronistically, and almost supernaturally sinister in his manner, like an avatar of the Devil after Connie’s living soul.

In this version of the story Arnold Friend doesn’t kill anybody – as far as we know. He stalks Connie and, eventually, convinces her to go for a ride. This is roughly where Oates’s story ends and in that version we’re left to speculate on her fate. But if you know it’s inspired by Schmid your speculation is likely to favour murder.

In the film, Connie returns. She is changed – an adult, now, and no longer innocent. But she is, at least, not dead and buried in the desert.

In almost every way Smooth Talk is the better film. Not least because it makes Friend/Schmid an exterior menace and puts in the turbulent mind of one of his victims.

The Schmids, they’re multiplying

There is something particularly dark and rich about this story which must be why filmmakers keep coming back to it.

There’s Dead Beat from 1994, which seems almost impossible to see; Lost from 2005, adapted from a novel by horror writer Jack Ketchum; and Dawn from 2014, which focuses on the sister of one of Schmid’s victims.

Schmid is not the only killer to have inspired multiple movies, though. In fact, it’s unusual for a notable serial killer not to have inspired multiple movies.

Leopold and Loeb are practically a sub-genre (Rope, Compulsion, Swoon). So is Ed Gein – the original model for six decades of psycho-slashers, from Norman Bates to Leatherface. And Badlands is by no means the only take on the Charles Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate story.

As a writer of fiction I find it almost maddening that real life generates stories that are so much more out there than anything I could invent. If I’d created Charles Schmid as a character it wouldn’t have occurred to me to give him white foundation make-up, a fake mole, and shoes full of crushed tin cans. Real criminals are often both dumber and more interesting than their fictional counterparts.

More importantly, I don’t know if I’d have been able to look at Schmid through the eyes of a teenager and have them think, “That guy is cool, I love him, I’ll do whatever he says.”

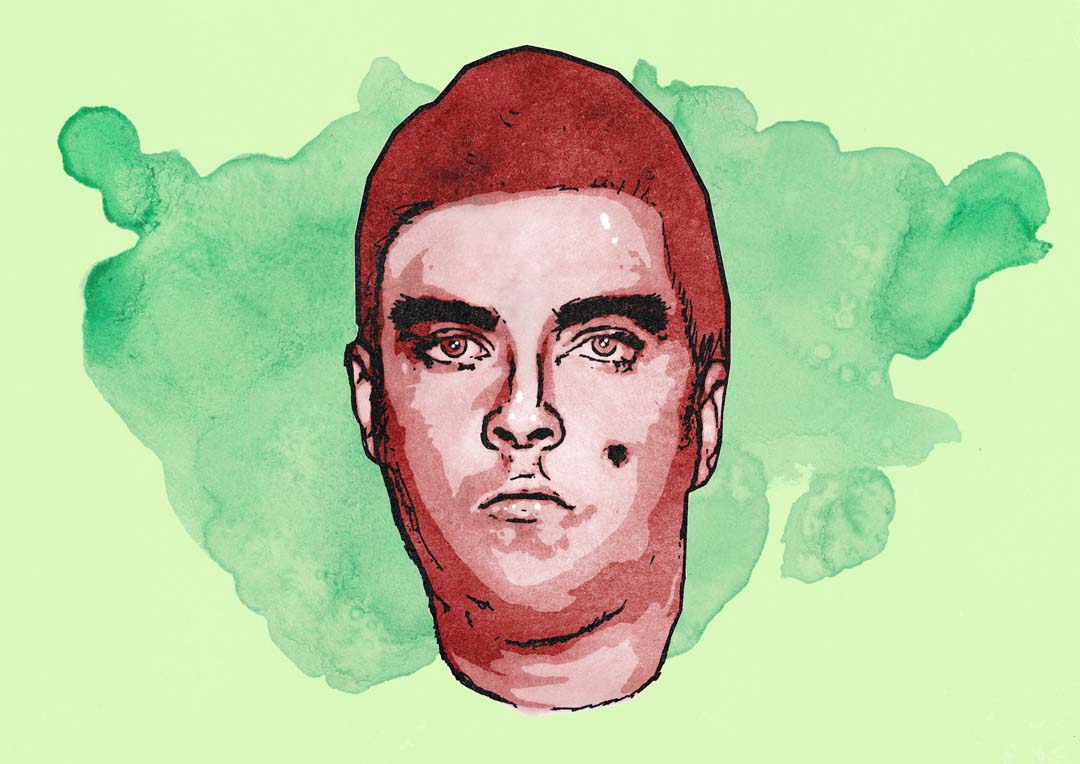

Main image: A digital sketch based on several different photos of Charles Schmid composited, traced, and treated with textures and filters.