I’ve never been to Los Angeles and probably never will. But it’s a city that exists as a high fidelity virtual model in our collective imagination as a result of more than a century of dominance over mass media.

What percentage of American films and TV shows are set in LA? A disproportionate number, I’m certain. And that’s before you take into account those that are filmed there even though they’re set in New York City, Las Vegas, Dallas, or wherever.

As a result, we all know aspects of Los Angeles’s landscape that would otherwise be insignificant to outsiders.

For example, there’s the concrete trough in which its river runs. Built to guard against flash flooding between the 1930s and 1950s it has since become a favourite location for filmmakers looking to shoot car chases and action sequences.

Griffith Observatory is another landmark that turns up in movie after movie, from Rebel Without a Cause to Bowfinger.

Watching Michael Mann’s 1995 film Heat for the first time this week I was struck by the deliberate choice of less frequently filmed locations, often quite anonymous. But even these spaces, beneath flyovers and in the car parks of malls, seemed familiar. If we haven’t seen these exact spots, we’ve seen similar ones in, say, episodes of T.J. Hooker, or Bosch.

Perhaps it’s because filmmakers so often live in Los Angeles that they so often make films about the city, or in which, as the cliché goes, “the city is a character in its own right”.

Films like To Live And Die in L.A. (William Friedkin, 1985) and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (Quentin Tarantino, 2019) present particular versions of the city. The former shows us a dusty Wild West city of backrooms, guard dogs, and industrial zones. The latter takes us back in time and attempts to magic back into existence the Los Angeles of the director’s childhood.

Model Shop (Jacques Demy, 1969), Cisco Pike (Bill Norton, 1972) and L.A. Confidential (Curtis Hanson, 1997) are all set in ostensibly the same city but each present it from a different perspective, in different light. There are a thousand others.

Together, they allow the outsider to begin to triangulate – to understand how the city fits together, and how it has changed over time.

L.A. Confidential is based on a novel by James Ellroy whose literary version of Los Angeles is both vivid and idiosyncratic. It’s similar to the city presented by Raymond Chandler in his Philip Marlowe novels, or by Chandler’s disciples in their LA private eye stories, only meaner and more brutal. Chandler’s LA is at least romantic, in a cheap, rather superficial way.

Chandler was an outsider, born in America but raised and educated in England, and looked at Los Angeles as if it were an alien planet. This is from The Little Sister published in 1949:

Real cities have something else, some individual bony structure under the muck. Los Angeles has Hollywood – and hates it. It ought to consider itself damn lucky. Without Hollywood it would be a mail order city. Everything in the catalogue you could get better somewhere else.

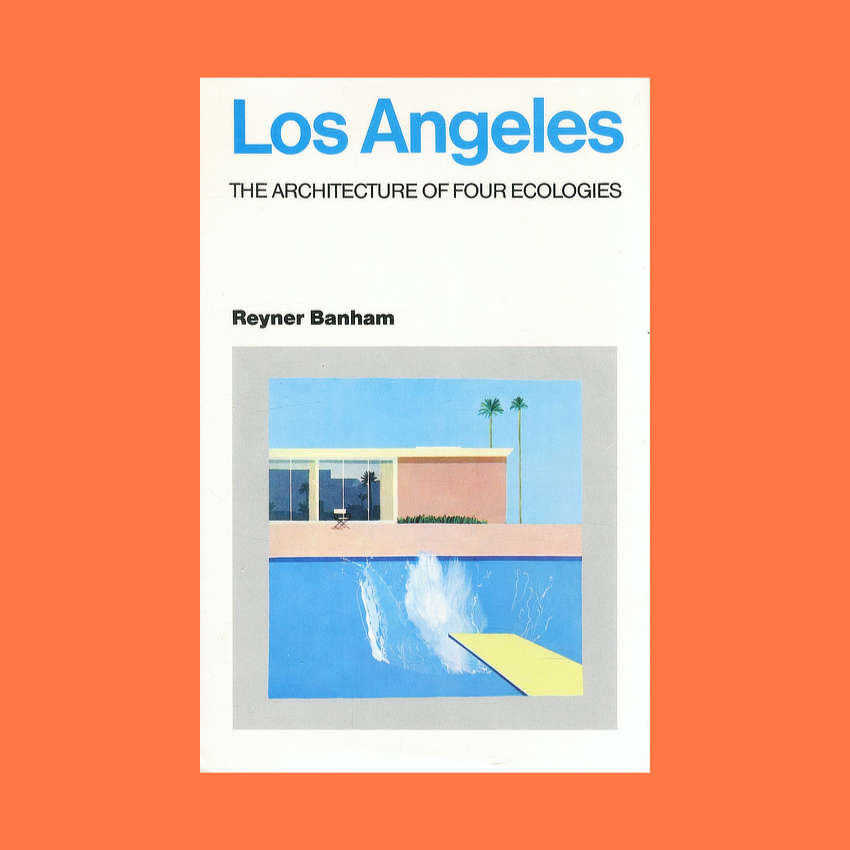

Another British writer who observed Los Angeles from a similar distance was critic Reyner Banham whose 1971 book Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies feels like a manual for understanding the city. Read a chapter or two and you’ll start to feel like an insider – as if you’ve seen LA’s top secret schematics.

Beyond literature and highbrow criticism, there are a million other ways that Los Angeles infiltrates the brains of people who live in, say, Luton, or Lübeck. If you listen to podcasts the chances are that you’ve heard the hosts fill the first ten minutes comparing notes on their drives to the studio, the weather, where’s good to eat, and how they’ve been effected by whichever natural disasters or episode of social unrest has most most recently occurred.

It’s an interesting aspect of the parasocial relationships we form with these strangers who murmur unscripted nothings in our ears every week for years on end.

Every month the excellent movie podcast Pure Cinema has an episode running down what’s showing at The New Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles. It’s interesting not only as a list of recommended viewing but also because of the ambient notes on life in the city, including casual asides about which actors have been spotted where, doing what.

Before podcasts there was radio and vast chunks of old radio shows from Los Angeles are now readily available on YouTube. As with podcasts, the pleasure here is in the snippets of chat between songs, and the evocative advertisements.

The songs, though, shouldn’t be ignored. Listening to The Beach Boys, The Byrds and The Monkees, as well as all those Nuggets fodder one-hit wonders, also transports you to Los Angeles.

British music fans talk casually about the Capitol Building and the crack session musicians later christened the Wrecking Crew. The most obsessed listen to hour after hour of bootleg recordings, absorbing the good vibrations of Gold Star Studios in the near silence between takes.

Surely with all of this data – all those episodes of Columbo and Adam-12 – at some point we’ll be able to conjure up a four-dimensional immersive model of a sunny Los Angeles we can wander about in, or even escape into for good.

There have been a few attempts already. The 2011 game L.A. Noire was an attempt to make the world of James Ellroy explorable and playable. To achieve that its creators, Team Bondi, recreated a vast swathe of Los Angeles approximately as it looked and felt in 1947.

It wasn’t perfect but in a rather moving article games journalist Chris Donlan wrote about playing the game with his father who grew up in LA in the 1940s. He found it pretty convincing:

The accuracy with which the city structures and roadways are recreated is really astounding, and the details were almost perfect… To be able to experience it again with my son who was born 20 years after I first left the city was, I think, wonderful for us both…

Then there are the several not-quite Los Angeles cities of the Grand Theft Auto games. The 2004 game GTA: San Andreas gives us Los Santos, an almost parodic version of LA circa 1992. The GTA V from 2013 develops Los Santos further, in higher fidelity, to the point where players were able to shoot their own films in its ultra-realistic environments.

If, like me, you’re not very good at games, there’s also Google Street View – a wonder of the age that so many of us take for granted. It’s easy to lose hours wandering jerkily from one street or roadscape to another, feeling both close to the city and impossibly far away.

Main image: a detail from a Los Angeles street scene by Lee Russell, 1942, by via the Library of Congress website.