The inspirations for this story about a delivery driver feel blindingly obvious to me – I wonder if anyone will see the connection?

First, there’s the nightmare logic of the films of Lucio Fulci and, in particular, The Beyond from 1981.

I find it hard to argue that The Beyond is a great film.

It has all the usual problems of Italian exploitation horror – bad dubbing, odd pacing, nonsense plot – plus the particularly dense layer of dinge and sleaze that seems to ooze from Fulci’s pores and over everything he makes.

So I’m not necessarily saying you should watch it.

But don’t be mistaken: I love it. At least, I keep rewatching it, and thinking about it.

Because, for all its flaws, it is full of breathtaking images, and its disjointedness begins to feel like a feature rather than a bug.

The ending, in particular, I find astonishing.

Our heroine and hero escape from pursuers by running into the basement of one building, only to find themselves in the basement of another, right across town.

This makes no sense.

What makes even less sense is that they then find themselves walking across an infinite plain strewn with corpses.

“And you will face the sea of darkness, and all therein that may be explored,” says the voiceover, gravely.

The other inspiration, very obvious, I think, is Robert Aickman’s wonderful 1967 story ‘The Cicerones’, in which a tourist explores a cathedral on the Continent and meets a series of unnerving tour guides as space and time distort around him:

Then something horrible seemed to happen; or rather two things, one after the other. Trant thought first that the stone panel he was staring at so hard seemed somehow to move; and then that a hand had appeared round one upper corner of it. It seemed to Trant a curiously small hand… the stone opened further, and from within emerged a small, fair-haired child… ‘Hullo,’ said the child, looking at Trant across the black marble barrier and smiling.

So, when writing ‘While You Were Out’, I kept challenging myself to make it not make sense in the same pleasing way.

To achieve this you really need to tap into the feeling of dreams or nightmares – the strange segues, the instability of objects or people, the sense of wading through glue.

The setting, a group of tower blocks on the edge of an English city, is not based on any one place but it does borrow from Barton Hill and Redcliffe in Bristol, where I live.

There’s also something of Gleadless Valley near Sheffield which I visited on a bleak November day a few years ago.

And the elevators, stairwells and corridors are straight out of various tower blocks I have known, including one in East London where my partner’s father lived for a while.

The chink of departing coin

When I wrote this post about being a working class writer last week it prompted writer Joel Morris to talk about characters who feel “the chink of departing coin”.

Bogdan, the delivery driver who is the main character in this story, is under pressure to meet unrealistic targets. And stress is part of what makes him vulnerable to strange experiences.

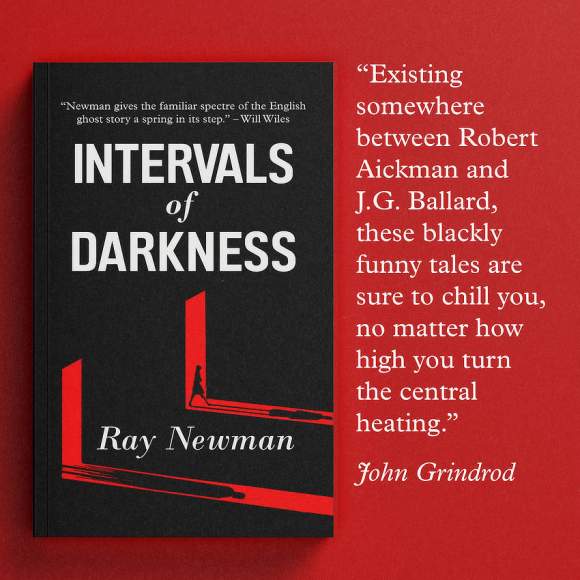

Throughout Intervals of Darkness there are characters who make bad decisions because they need the money. As well as feeling true to life – or, at least, true to my own experiences – this also brings a new energy source to the stories.

One of the characters in ‘British Chemicals’, for example, takes speed and works through his break periods because he’s just become a father and needs all the overtime he can get.

Intervals of Darkness will be published on 7 September. You can pre-order the eBook now.