Sleeve notes for a Blu-ray box set that doesn’t exist.

In April 1969 the British film director Bryan Forbes became head of EMI Films in the UK. His statement of intent summed up a particular view of the state of the national film industry at the time:

We have gone too far with pornography and violence… There is simply no reason why filthy violence should be dragged into pictures. You do not have to lower your sights to entertain. We must see to it that entertainment does not become a dirty word.

Meanwhile newspapers were full of talk about “the permissive society”. More specifically, they were asking “Has it gone too far?” Here’s Rosemary Simon in an article in the Illustrated London News:

The saddest aspect of the whole situation is the needless waste. Healthy boys and girls who channel their energies into creating a disturbance instead of concentrating on sport, work, or helping in the community… Attractive girls with their whole future before them who, instead of enjoying their youth and eventually getting married, find themselves pregnant and are faced with the tragic alternative of seeking an abortion of of giving birth an illegitimate baby.

Tabloid newspaper The People reported that its readers had come out 4 to 1 against the permissive society based on the sentiment of correspondence received, like this letter:

A housewife has to try to make a happy home knowing her husband is queueing up to go to work beside a see-through, bra-less, mini-skirted girl… that he chats up a topless barmaid at his pub, while he spends the evening at his club watching strip-tease… If he can afford it, a sexy girl will even cut his hair. Unless he is made of stone he must get involved somewhere… A housewife feels hurt, inadequate, dreary and cannot compete. This is where the children begin to suffer. – Mother of four. Name and address supplied.

That’s terrible, said the public. Appalling. Tell me more. Like, what exactly are they getting up to, these dirty bastards?

In this context British films walked a difficult path. They knew people wanted to see films with sexual content, especially if it was transgressive. But couldn’t be seen to condone it.

So they made films which suggested sexual liberation had gone wrong, that perversion was rife, and that this was a serious Problem of Our Age… while also depicting it more or less frankly, with actors who were more-or-less lovely to look at.

Like American films of the 1930s and 40s who had to make gangsters pay for their crimes to justify the preceding hour of swagger and violence, British ones of the late 1960s had to make sure the swingers suffered for their pleasure.

A cinematic uniperverse

There are a slew of films from 1968 to 1972 that aren’t formally related but which catch a similar mood and bounce off each other.

They sometimes share cast members, or at least types – ostensibly angelic blonde youths frequently feature, for example, as do sexually confident older women, and kinky establishment men.

Most of them are set in and around London and use the city to highlight the contrast between the old world (decaying, Victorian, Gothic) and the new: motorways, modernist towers, coffee bars, discotheques and pop art pads.

Their soundtracks steal from pop music of the period while always being a little too square, more Alan Hawkshaw than Mick Jagger, straight off the library shelf.

As for the tone, it’s about sickness. Yes, they’ll show you pretty young things with their kit off, to varying degrees, but they’ll also make you feel slightly queasy.

Brothers and sisters put hands and lips where they shouldn’t. People sweat and fret, suffering from physical and/or mental wounds. They mix sex and death at every opportunity. And adults frequently behave and even dress like children – which says what about their lovers?

Is it ever sexy? Fleetingly, sometimes, but more often it feels like the aversion therapy Alex undergoes in A Clockwork Orange.

Georgie likes ducks

The film that feels to me like the start of this run is Twisted Nerve (dir. Roy Boulting, 1968) starring Hywell Bennett as a baby-faced blonde psychopath called Martin.

Barry Foster plays a lecherous lodger employed in the film industry, who says at one point: “If you want me to sell your crummy films, I say you’ve gotta give it a good dose of S&V. That’s what the public wants. Sex and violence.”

What a disgusting attitude, we are invited to think, before gorging on our own helping of S&V.

At the time, the controversy around Twisted Nerve centred on its treatment of the subject of Down’s Syndrome and its tangling of chromosomal conditions with mental illness. That’s even less comfortable for viewers today.

But it exactly demonstrates the tendency of these films to balance turn-ons with turn-offs. Twisted Nerve starts with Martin engaged in an extended discussion with a doctor about his brother’s incontinence, likely early death and parental abandonment. It’s pointedly bleak.

Martin then adopts, or rather inhabits, an alternate personality – Georgie, a childlike character presumably based on Martin’s observations of his own brother. As Georgie, he stalks Hayley Mills and inveigles his way into her home. He then seduces her mother (Billie Whitelaw) who, remember, is up for it, despite believing that he has the mental capacity of an eight-year-old.

Martin is sick but so is almost everyone else, including his own respectable but uncaring parents.

An infamous double bill

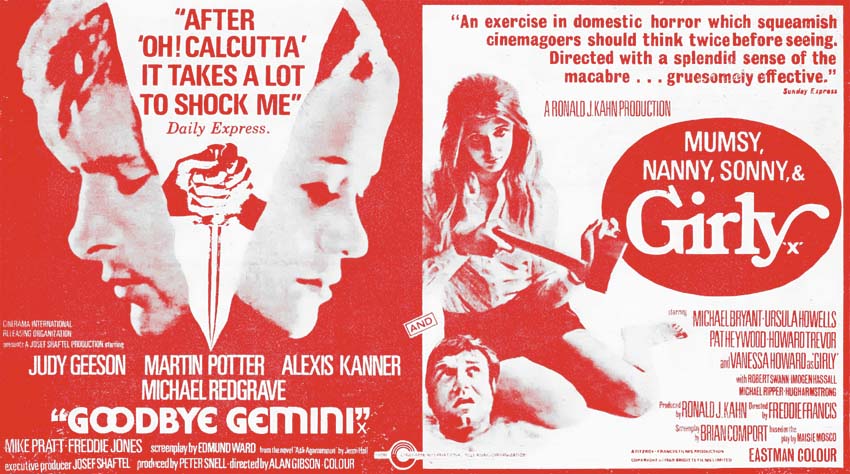

It’s astonishing that two of the key films in this cycle were released simultaneously and often shown together as a double bill. That is Goodbye Gemini (dir. Alan Gibson) and Mumsy, Nanny, Sonny & Girly (dir. Freddie Francis) both released in 1970.

Of the two, Mumsy, Nanny, Sonny & Girly is the better and more interesting film. It tells the story of a strange family – or is it a cult? – living together in a large country house.

The matriarch (Ursula Howells) and her servant (Pat Heywood) run the house while Girly (Vanessa Howard) and Sonny (Howard Trevor) run around in school uniform playing The Game.

To play The Game, you need playmates, so they occasionally go out into the world to seduce or bamboozle vulnerable men into joining them at the house. Those men are imprisoned and played with until they break the (impenetrable, unwritten) rules, at which point they are murdered.

When this film was released in the US it had a new title – Girly – and Vanessa Howard was the focus of the marketing. Dressed as a schoolgirl, the then 22-year-old actress sometimes plays the character as a seductress, and at other times as genuinely childlike. The audience is invited to fancy her, then to feel unclean for having done so.

It’s a grubby, disturbing, slimy film that makes my skin creep in the same way as Death Line, only without the gore. The other comparison might be The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, which also finds horror in twisting the traditional family structure.

Goodbye Gemini is more generic. It opens with rapidly cut shots of a coach arriving in London along the motorway, soundtracked by thumping Hammond-driven rock music. It’s meant to tell us we’re arriving in the big city, in the modern world, but of course it all looks a bit damp and tatty.

Judy Geeson and Martin Potter play cute blonde twins Jacki and Julian. They’re in their late teens or twenties but act younger, often deferring decisions to their teddy bear, Agamemnon. Decisions such as whether to throw the housekeeper who’s supposed to be looking after them down the stairs, for example, so they can enjoy London without restraint.

Julian loves Jacki a bit too much, in a way that’s not healthy. For a while, they share a boyfriend, hippy hipster Clive, who also wants to be Julian’s pimp. To seal that deal, he arranges for him to be raped by two men. So Julian and Jacki arrange for Clive to die. And so on into ever-descending spirals of blood and hysteria.

It’s a sweaty, feverish, unsettling film that tells us sex is a nightmare, love is a sickness, and that only death can set us free. It was also released under the name Twinsanity which is less tasteful but gives a clearer idea of its tone.

Sickness is in, baby!

There are plenty of other films that fit alongside those mentioned above, many of them included in the excellent book Offbeat edited by Julian Upton, which presents an alternative canon of British film.

I’ve already mentioned Dracula AD 1972 which brings Dracula to modern-day swinging London. Here, the obligatory handsome blonde boy with a black heart is Johnny Alucard (Christopher Neame). His sickness takes the form of a master-slave relationship with Dracula himself. You could take Dracula out of the equation and retool this as a story about a delusional psychopath loose among the hipsters of Chelsea with relative ease. Like Goodbye Gemini it opens with shots of London – jet planes, flyovers, tower blocks – accompanied by pounding rock-funk. The following year’s The Satanic Rites of Dracula, also directed by Gibson, provided more of the same, with the addition of a satanic sex-power cult.

What Became of Jack and Jill (dir. Bill Bain, 1972) has Vanessa Howard, AKA Girly, as one half of a murderous young couple opposite Paul Nicholas. They shag on his granddad’s grave as they plot the murder of his grandmother. Their plan is to scare her to death by convincing her that the young are rioting in the streets and rounding up the elderly.

Unman, Wittering & Zigo (dir. John Mackenzie, 1971) isn’t set in London but transplants swinging London icon David Hemmings to a public school in the country. His pupils, arrogant little bastards, tell him they killed his predecessor and will kill him if he doesn’t submit to their will. As they engage in a battle of wills, the boys stalk and eventually attempt to rape his wife. Sonny from Mumsy, Nanny, Sonny & Girly would fit right in. He might even make a good pal for the unfortunately marginalised Wittering.

Jerzy Skolimowski’s Deep End from 1970 is beautifully made – definitely more art than exploitation. But it still gives us the beautiful blonde boy with a kink in his brain (John Moulder Brown), sexual relationships that cut uncomfortably across age barriers, and sex scenes that are more disturbing than arousing. He plays Mike, a 15-year-old boy who gets a job at a swimming pool in East London. On day one his colleague Susan (Jane Asher) initiates him into a job on the side pleasuring older women in the sauna rooms. He is driven mad by his infatuation with Susan and their complex relationship (she rejects him, then brings him close) leads to the inevitable mingling of sex and death.

The Ballad of Tam Lin (dir. Roddy McDowall, 1970) cuts across sub-genres. The first act takes place in that familiar, slightly square version of swinging London with beautiful young things in mod clothes speeding around in sports cars. The sequence in which they race out of town, past the modern office blocks of London Wall and up the M1, recalls the opening scenes of both Goodbye Gemini and Dracula AD 1972. They are the acolytes of a beautiful older woman (Ava Gardner) who seems to draw strength from their youth. There’s no room for dead weight in her commune-cult, though, and we see that she uses people up and discards them. The second half of the film fits more comfortably into the folk horror bracket, however.

These films are all quite different, I realise, in both intent and quality, but you could pick any two and run them together as an effective double bill.

When I asked people on Twitter about this they suggested a whole slew of other candidates. I’ve compiled those, along with the films listed above, into a watchlist on Letterboxd. Let me know what’s missing.

One reply on “Goodbye Aquarius: how sickness, sex and death got tangled up in British films 1968-72”

Night Hair Child / What the Peeper Saw is a monumentally grubby little film

LikeLike